|

Margate before Sea bathing: 1300 to 1736

Anthony Lee

Chapter 6: Riots and Wars

Riots

In June 1381 the Peasants’ Revolt, the major uprising of the Middle Ages, broke out, mainly in southern and eastern England, the wealthiest parts of the country, and despite its name, involved towns as well as countryside.1,2 The background to the riots was a simmering discontent with the local gentry and the Church and the ways in which they tried to control the lives of the poor, some of whom were unfree serfs forced to work on their lord’s lands for a period of time each year. What finally sparked off the riot was, however, the imposition of a poll tax on both rich and poor. Under the leadership of Wat Tyler the Kentish rebels marched on London to be joined by rebels from Surrey and Sussex. There, with the support of the London mob, they unleashed an orgy of destruction, freeing prisoners, lynching lawyers, and burning buildings; the chancellor and treasurer of England were seized and summarily beheaded. King Richard II, then only 14 years old, conceded the rioter’s demands and granted a free pardon to all, although Wat Tyler was killed in a scuffle with the Lord Mayor of London. The rebellion lasted only a few days before the authorities regained control and executed the leaders of the revolt.

In Kent the rebellion started in early June. Sir Simon de Burley, a courtier close to Richard II, had imprisoned a Kentish man, Robert Belling, in Rochester Castle, claiming that he was a serf escaped from one of his estates. After a meeting at Dartford, a large crowd travelled to Maidstone, where they stormed the gaol, reaching Rochester on 6 June, breaking into the Castle and releasing Belling. Although many of the rebels then dispersed, some, under the leadership of Wat Tyler, advanced to Canterbury, entering the city without resistance on 10 June. There they attacked properties in the city, murdered the Archbishop, Simon Sudbury, and others they considered to be their enemies, and released prisoners from the city gaol. The next morning Wat Tyler with several thousand rebels left Canterbury and proceeded to London. Inspired by the arrival of Wat Tyler and the rebels in Canterbury, the Thanet revolt broke out at St Lawrence (Ramsgate) on 13 June and at St John’s on 24 June, that at St John’s being led by a local curate, William ate Stone the younger.3 At St Lawrence six men, including ‘John Tayllor, Sacristan of the Church of St John in Thanet, and John Bocher, Clerk of the said church of Thanet’, made a proclamation that the house of William Medmenham in Manston should be attacked; Medmenham was Steward of several Manors and keeper of their Court Rolls, as well as Receiver of the King’s Taxes for the County of Kent. The intention was not only to burn his rolls and books but to pull down his house and, if they could find him, to ‘kill him, and cut off his head from his body’. A crowd about 200 strong attacked his house. They ‘feloniously broke open the gates, doors, chambers, and chests of the said William and carried away his goods and chattels to the value of twenty marks’ and burnt his ‘books and muniments’ but, fortunately for him, did not find Medmenham himself. The proclamation made at St John’s on 24 June was milder, ‘that no tenant should do service or custom to the lordships in Thanet, as they have aforetime done’. On 8 July Medmenham’s house in Canterbury was also looted and John Boucher [Bocher], the clerk at St John’s, led a raid on the Canterbury house of John Wynnepeny ‘and feloniously compelled him to pay a ransom of thirty-two shillings’.3

The enquiry into these events was heard by two jurors of the Hundred of Ringslow, William Daundelion (Dent-de-lion) and Thomas Edrich and three constables, Stephen Colluere (Collier), Gervase Saghiere (Sayer) and Simon Fygge, and are recorded in ‘Presentationes de Malefactoribus quie surrexerunt contra Sominum Regem, 4 et 5 Ric. II’.3 Two presentments relate to the rebels at St John’s:

I. Presentments of malefactors who have risen against our Lord the King (4. and 5. Ric. II.)

Be it remembered, — that, on St John the Baptists Day, in the fourth (fifth) year of the reign of King Richard the Second after the conquest (June 24th, 1381), at St John’s (Margate) in Thanet [Tanet], William Tolone, John Jory, Stephen Samuel, William atte Stone the younger, and John Michelat, raised a cry, that no tenant should do service or custom to the lordships in Thanet, as they have aforetime done, under pain of forfeiture of their goods and the cutting off of their heads. And also, that they should not suffer any distress to be taken, under the above-said penalty.

And also, the aforesaid men raised another cry, on the day of the Feast of Corpus Christi, in the above-said year (June 13, 1381), at St Laurence in Thanet, that every liege man of our Lord the King ought to go to the house of William Medmenham, and demolish his house and level it with the ground, and fling out the books and rolls found there, and to burn them with fire, and if the said William could be found, that they should kill him, and cut off his head from his body, under like penalty; and they ordered a taxation to be paid for maintaining the said proceedings against the lordships throughout the whole Isle of Thanet, except the tenants of the Priory of Canterbury and the franchise of Canterbury.

By virtue of which cry, the Jurors of the hundred of Ryngslo say, that these same entered the house of the said William, and burnt the aforesaid rolls and books, and did no other harm to the said William.

And further they say, that they raised the cry that no tenant should do service or custom, as is above said, and that they made the taxation.

RYNGSLO to wit

The Jurors to inquire concerning the malefactors who rose against our Lord the King and his people, from the Feast of Trinity, in the fourth year of the reign of King Richard the Second, continuing at intervals, from the day and year aforesaid until the morrow of Corpus Christi next ensuing (from June 9 to 14, 1381), say, upon their oath, that William the Capellan, officiating in the Church of St John in the Isle of Thanet, and Stephen Samuel, on Thursday in the Feast of Corpus Christi in the aforesaid year (13 June, 1381), rose and proclaimed, against the peace of our Lord the King, that all and singular ought to unite, and go to the house of William Medmenham, under the penalty of death and the forfeiture of their goods and chattels, and to pull down the house of the said William Medmenham. Whereupon, the aforesaid William and Stephen entered the house of the aforesaid William Medmenham, on the day and year aforesaid, together with others who were driven by them to this, and burned the books and muniments of the foresaid William Medmenham at Manston, in the foresaid Island, to the damage of the said William of twenty shillings. The rest well.

Custodes of the said Hundred,

William Daundilioun,

Thomas Eldrych.

Names of the Constables,

Stephen Coluere,

Gervis Saghiere,

Simon Fygge.

There is no evidence to suggest that any Thanet men were involved in the riots in London, and none are recorded amongst those hung, although six men from Canterbury were.4

A second revolt occurred in Kent in 1450, led by Jack Cade. This revolt was centred on Ashford and at least eleven Thanet men were involved.4 Their grievances included local concerns such as the perceived corruption of the Dover courts and corruption surrounding the election of knights of the shire, and more general concerns such as anger over the debts ran up to pay for years of warfare against the French. Cade marched on London but, when the rebels started to loot the city, the citizens turned on them and forced them out. Cade fled but was fatally wounded in a skirmish with Alexander Iden, a future High Sheriff of Kent. There is no evidence to suggest that the inhabitants of the Cinque Ports took any concerted part in this rising.5 A further riot occurred in 1495 following the introduction of a new statute to replace the national wage rates for labourers established in 1446.6 Disturbances occurred in Wingham, to the east of Canterbury, and in the parish of St Nicholas at Wade, in the Isle of Thanet. Nine men were indicted for the disturbances, but it was suggested that at least 160 men were actually involved in the Isle of Thanet.

Wars

|

Figure 32. Margate Roads, from a map of the Thames ca 1840. |

Margate’s position on the coast gave it a strategic importance. Margate Roads, a deep-water anchorage just north of Margate, protected on the seaward side by the Margate Sands, was used by the Royal Navy as a fleet anchorage and to guard the mouth of the Thames (Figure 32). On the cliffs to the east of the harbour at Margate was a small fort built to protect both the harbour and ships going round the North Foreland into the Downs. In the twelfth century the need to protect the English Channel led to the formation of the Confederation of the Cinque Ports, a confederation consisting of the five ports of Hastings, New Romney, Hythe, Dover and Sandwich (Chapter 5). We know that Margate had become a non-corporate member of the Cinque Ports by 1229 as an ‘ordinance touching the service of shipping’ issued by King Henry III in 1229 listing ‘the Ports of the King of England having liberties which other ports have not’ included ‘Dover, to which pertaineth Folkstone, Feversham, and Margate, not of soil but of cattle’; unfortunately the meaning of the phrase ‘not of soil but of cattle’ has been lost.7,8 The original charters specified that Dover, with the help of its corporate and non-corporate members, was to provide for the King ‘twenty-one ships, and in every ship twenty-one men with one boy, which is called a gromet’, the word ‘gromet’ coming from the Dutch word Grom, meaning a stripling. These ships were to be provided each year ‘for fifteen days at their own cost’ the fifteen days to be counted ‘from the day on which they shall hoist up the sails of the ships to sail to the parts to which they ought to go’.

The agreement to provide just twenty one men and a boy for each ship might have been sufficient when the ships were just 30 to 60 tons, but by the fifteenth century most naval ships were of 100 tons, needing crews of at least 65 men.5 These large fighting vessels were either specially built royal ships or large impressed merchant ships from ports on the East and West coasts; the ships provided by the Cinque Ports, mostly fishing vessels, were by then used mainly for relatively menial transport purposes. As emphasised by Murray: 5

During the thirteenth century the reputation of the [Cinque] Ports’ fleet was established, but as pirates rather than a national force: their importance was temporary, arising out of a condition of civil war and the fact that their profession as fishermen involved the possession of seaworthy vessels available in an emergency when other sources failed. The terms of their service were unsuited to the big naval expeditions which became more common in the fourteenth century. They were only bound to serve for fifteen days at their own costs, and this time was often spent in reaching the meeting-place before the campaign began . . . In expeditions of this kind the Cinque Ports played no special part; they were not exempt from general service with the impressed ships of other ports, and their boats formed only a fraction of the total fleet.

As the Cinque Ports lost naval power and, with it, effective control of the Channel, they also lost political influence; when a royal navy came to be built its headquarters were at Southampton, and not in the Cinque Ports.5 This loss of importance is clear in the small numbers of ships provided by the Cinque Ports for the continental campaigns of the fourteenth century. The Cinque Ports provided just 36 ships crewed by 1,084 mariners in 1325 to transport the forces of Edward II to Gascony, and in 1326 their contribution was just 35 ships, 26% of the total, manned by 1,262 mariners, 46% of the total, none of the ships apparently coming from Dover.9 Indeed, this earned the constable of Dover castle a rebuke from Edward II: ‘Although the king ordered the mayors and bailiffs of the towns of Hethe, Dover, and Faversham, which are within the liberty of the Cinque Ports, to cause all owners of ships of those towns and the members thereof of the burthen of 50 tuns and upwards to come to Portesmuth with their ships on Sunday after the Decollation of St John the Baptist last, to set out in his service for the defence of the realm against the attacks of the French . . . the said mayors and bailiffs have not hitherto caused certain of the ships to come to the said place’.10 As a sign of his displeasure:10

the king has now ordained that twelve ships of Kent and the city of London, each provided with 40 armed men and victuals and other necessaries, of the ships that have not come to Portsmouth, shall remain on the sea coast near Forland in the Isle of Thanet for the repulse of the French and other enemies, if they endeavour to enter the realm there, at the cost of the men of the towns to which the ships belong who shall have no ships there, and have no part in the ships, and are not now in the king’s service aforesaid, whilst other ships that have come to that place by virtue of the orders aforesaid and that have set out in the fleet . . . shall remain in that service; of which twelve ships the king wills that two shall be of the town of Hethe, two of the town of Dover, and the fifth of the town of Faversham; the king therefore orders the constable to cause the said five ships to be chosen out of the best ships of those towns that have not set out in the king’s service as is aforesaid, and to cause each of them to be provided with 40 armed men and victuals and other necessaries at the expense of the aforesaid men, and to cause the necessary charges for the mariners and armed men to be levied, and to cause the ships to come to the coast aforesaid, so that they be there on Sunday the feast of St Matthew next at the latest.

The Cinque Ports also contributed little to the great naval engagements of the Hundred Years war lasting from 1337 to 1453. For example, at the siege of Calais in 1347 only about a quarter of the Southern Fleet came from the Cinque Ports, Margate providing 15 ships and 160 mariners and Dover 16 ships and 336 mariners; the relative numbers of mariners per ship emphasises how small the Margate ships were, even compared to those of Dover.5,11 The cost of the war with France was immense, and large numbers of merchant vessels were impressed for these expeditions, some 735 for the siege of Calais in 1347. Merchants whose ships had been impressed would, of course, try to get them back as quickly as possible. In 1343 Edward III ordered the arrest of a large number of ships that ‘went with the King to Britanny’ but ‘departed from the port of Brest, where the King landed, contrary to his prohibition’.12 Of these ships two were from Margate, la Godbiete and la Luk, Simon Lioun and Salomon Lithere, masters.

In 1544 Dr Richard Layton, Dean of York and Henry VIII’s agent in Flanders, was requested by the privy Council to ‘prest 200 hoys’ to provide transport for the war with France over Boulogne; it was reported that he had managed to press ‘10 for Margate’. These hoys were from 110 tons down to 35 tons and were each large enough to carry between 30 and 35 horses.13,14When a survey of the ships at Margate was taken in 1584 as part of the preparation for the abortive expedition sent to Flanders, only one of the 12 was listed as suitable for carrying ordnance, and that was a barke of 70 tons (Appendix X).15 Eventually Margate ceased to provide any of the 21 ships that Dover had to contribute to the Navy, making instead a cash contribution to Dover every year.16 However, in 1628 Margate did provide one hoy to the fleet used in the relief of la Rochelle:17

Whereas there are imprested for his Majesties service twenty Hoyes and Catches, being to attende the Fleete which is to be employed for the reliefe of Rochell, although six of that number, viz. the Mary of Margat, the John, the Marygold, the Samuell, and the Michell of Sandwich and the Edward of Feversham, belonging to places within the jurisdicion of the Cinque Ports; yet in regarde of the present and necessarie use of them, there being no other meanes to have a sufficient number of such vessels: It is hereby ordered that they shalbe employed in his Majesties service, for which they are imprested notwithstanding anie priviledge or direction to the contrarie: Whereof the principal Officers of the Navy are hereby required to take notice, and to see the same performed accordingly.

The Home Guard

The strategic importance of the Isle of Thanet meant that it needed to be properly protected at times of war, but until late in the seventeenth century England had no standing army. In the same way that the inhabitants of a town were expected to enforce law and order themselves, as there was no police force until the nineteenth century, so every able-bodied Englishman was required by law to be prepared to fight in defence of the realm. In April 1338, at the start of the hundred years war, Edward III ordered that all archers in Kent should be sent with the King’s forces to France, except for those living close to the coast, who were to stay where they were: ‘Order not to lead any archers away from the maritime parts of that county, to wit, within 12 leagues of the sea, but to permit them to stay there to repel attacks’.18 An order of May 1338 made it explicit that this order applied to the Isle of Thanet:19

To the electors and arrayers of archers for the king’s service in co. Kent. Order to supersede the leading of archers out of the isle of Thanet, but to permit them to remain there for the defence of the island, while danger is imminent or until further orders; the king also orders them to elect as many archers as they elected in the island, elsewhere in the county and to lead them to the town of Great Yarmouth, to be there on Wednesday in Whitsun week next at latest, as the men of the island have besought the king to order such archers to stay there and to provide for the assistance of other men for the defence of the island, as aliens in galleys and ships of war are ready to invade the island, thinking to do injury there more quickly than elsewhere.

Also in May 1338 Edward III made it clear that he wished the large local landowners, ‘the abbots of St Augustine’s, Canterbury, and Faversham, and the priors of Christ Church, Canterbury, Dover, and Rochester’ together with ‘priors, earls, barons and others in Kent and Sussex having land near the sea coast, to cause their servants and others of their retinue to be arrayed at arms, and to be led to their manors near the sea and to stay there for the defence of the realm’ because ‘certain aliens of France, Normandy and elsewhere have assembled a great fleet of galleys and ships of war to attack the realm’.19 It was recognized that concentrating so many men close to the coast might result in a shortage of food and so it was also ordered that the forces going to France should not take ‘any victuals except wine within 12 leagues of the sea in co. Kent, while there is danger of foreign attack there, and while the lieges are staying there for the defence of those parts’.18

The threat to the coast was real; in March 1338 a large French force took Portsmouth and, having plundered the town, set it alight, and in October the French, supported by their Scottish allies and by Genoese mercenaries, landed at Southampton and sacked that town as well. In 1339 the French forces sailed up the coast as far as the Isle of Thanet, and Hastings, Thanet, Folkestone, Dover and Rye were attacked and partly burnt; it was reported that the French ‘were prevented from doing much mischief, except to the poor’.11 An order was given in 1339 that some of the men of Sarre should remain on the Isle of Thanet for its defence:20

To William de Clynton, earl of Huntingdon, constable of Dover castle and warden of the Cinque Ports and of the maritime land in co. Kent. The mayor and community of Sandwich have shown the king that although they have ordained ships of that town to set out to sea with the fleet towards the west, for the defence of the realm, and certain men of Sarre in the isle of Thanet, a member of the port of Sandwich, are ordained to set out in those ships, yet the men assert that they are staying in the island for its defence by order of the keepers of the island, and are forbidden by them to leave the island, and it is more expedient for them to remain in the island for its defence than to set out in the said ships, and they excuse themselves to the mayor and community who have besought the king to cause those men to set out; the king orders the warden that if the town is a member of the port of Sandwich, then to cause certain of those men to set out in the fleet, as he sees fit, and certain to remain in the island.

In July 1345 ‘measures were taken for the protection of the Isle of Thanet, in consequence of the French, whom the King styled his "enemies and rebels," having collected numerous ships, galleys, barges, and flutes, for the purpose of landing on the English coast, to commit all kinds of injuries’.11 In 1378, although a truce had been negotiated with the French, ‘lest the French should again invade England, on 16 March a general array of soldiers was made in the Isle of Thanet to prevent the enemy from landing there’.11 In 1385 the English army invaded Scotland but was driven off by the joint forces of Scotland and France, a situation made worse by the threat of an attack on England’s southern coast by the French fleet. The need to defend the Kent coast was urgent, and was to be paid for by a tax of 1d on every basket of fish landed at the ports:21

January 18 1385, Westminster

Appointment of Simon de Burley, constable of Dover castle and warden of the Cinque Ports, John de Cohham of Kent, John Devereux and Edward Dalyngrugg, upon information that the French with a large army intend to land within the liberty of the Cinque Ports to destroy them, to levy from the seller a penny upon every basket of fish coming to Rye, Wynchelse, Hastynges, Promhell, Lyde, Pevenyse, Romene, Hethe, Folkstone, Dele, Walmere, Recolvere, Wytstaple, Sesaltre, Mergate in the isle of Tenet, Redlyngweld, Bourn, Codyng, Bolewarehethe, Iham, Odymere and Plvdenne, and to expend all sums arising therefrom upon the defence of those ports and the country adjacent, and to take masons, carpenters and labourers for the fortifying of Rye, with power to arrest and imprison the disobedient until further order.

For whatever reason the level of the tax seems to have been changed, before implementation, to ‘3d on every noble’s worth of fish landed’ (a noble was a gold coin worth 6s 8d, or a third of a pound sterling).21

Also in January 1385 it was ordered that all the able-bodied men in Kent were to proceed to the coast ‘and other places where danger threatens’, and that the beacon warning system should be overhauled:22

Commission, in view of imminent invasion by the French, to Simon de Burle, constable of Dover castle, John de Cobeham, John Devereux, Arnald Savage, Thomas Brokhull, Roger Wygemore, Thomas Sbardelowe, John eta Frenyngham, James de Pekham, Richard de Berham and the sheriff of Kent, to array all men-at-arms, armed men and archers who live in that county, and arm all able-bodied men, both those who have the wherewithal to arm themselves and those who have not, each according to his estate, and to assess, apportion and distrain all who in lands and goods are capable but by feebleness of body incapable of labour, to find armour in proportion to their lands and goods, and to contribute to the expenses of those who will thus labour in defence of the realm, those staying at their houses for the purpose of defending them are not to take wages nor expenses therefor. These men-at-arms they are to keep arrayed and to lead to the sea coast and other places where danger threatens, and if any resist they are to arrest and imprison them until further order. Moreover the signs called ‘Bekyns’ are to be placed in the accustomed spots to warn the people of the coming of the enemy.

By April 1385 the threat of invasion was thought to be so serious that all the inhabitants of the area were ordered to go with their families to Dover castle, Rye or Sandwich for protection:23

Appointment until All Saints, of Simon de Burle, constable of Dover castle and warden of the Cinque Ports, upon information that the king’s enemies of France, Spain, Flanders, and Brittany are leagued together to destroy the people and fortalices on the English coast by an invasion within a brief time, to cause proclamation to be made in Sandwich, Dover and Rye, and all places where he shall deem it expedient within the islands of Thanet and Oxeye and six miles round Dover castle and the said towns of Rye and Sandwich, that all the inhabitants within those islands and six miles round, with their families and goods, withdraw before 3 May under pain of imprisonment to the said castle and towns for safety, ecclesiastics only excepted.

Presumably the order must have been withdrawn a few weeks later when the expected invasion failed to occur. Anyhow, the order was re-imposed on April 31 (sic) 1386, withdrawn on May 14 and then again re-imposed on June 18, when the inhabitants were ordered to take their victuals with them.24,25 The policy was clearly to stop people from fleeing inland and to concentrate manpower at the major ports where they could mount an effective defence. Nevertheless, in February 1392 it was reported that people were leaving the Isle of Thanet because its defences against enemy landings were in ruins:26

Commission of oyer and terminer to Arnald Savage, William Rikill, William Makenade, Nicholas atte Crouche, Stephen Bettenham, William Elys, William Berton and William Titecombe, on information that inhabitants of the isle of Thanet having lands and houses therein are continually leaving it, and that the turreted walls both upon and below the cliff of the island, as well as certain dykes formerly constructed there for defence against hostile attacks, are weak and in ruins, while divers persons who are bound to repair the causeways of the ferry on either side of the water of Serre and to find and maintain boats and other vessels for the passage and carriage of men and animals have long neglected to do so. They are to examine the condition of the island in all these respects and enquire who are bound to find boats and vessels, repair the causeways and walls and cleanse the dykes, and compel them thereto and to stay in the island or find others in their place for its defence.

In March 1410 a renewal of hostilities seemed so likely that a commission of array was issued to the abbot of St Augustine’s and other senior county figures for the defence of the Isle of Thanet, a commission of array being a commission issued to the local gentry to muster the able bodied men of an area for its defence:27

Commission of array to the abbot of St Augustine’s Canterbury, Arnold Savage, Richard Cliderowe, Robert Clifford, William Notebem, John Whithede, John Dreylonde, Thomas Marehaunt, John Scheldwych, and the sheriff of Kent within the Isle of Thanet for defence against the king’s enemies.

In 1451 another muster ‘of all men at arms, hoblers and archers’ was taken in the Isle of Thanet and at the same time the beacons were put in order:28

Commission to George, abbot of the monastery of St Augustine by Canterbury, William Manston, Roger Manston, John Septvans and Thomas Saintnycholas, appointing them to array and try all men at arms, hobelers and archers within the isle of Thanet and to lead them to the sea coast and other places in the Island to resist the king’s enemies, and to take the muster of the same from time to time, and to set up ‘bekyns’ in the usual places and cause wards and watches to be kept, arresting and imprisoning such as refuse to keep the same, until they find security for their obedience.

Simply mustering large numbers of the local men would not be sufficient to ensure the safety of the country if those men were untrained in the use of weapons. On 1 June 1363, Edward III wrote to his sheriffs and commanded:29

[a] proclamation to be made that every able bodied man on feast days [including Sundays] when he has leisure shall in his sports use bows and arrows, pellets or bolts, and shall learn and practise the art of shooting, forbidding all and singular on pain of imprisonment to attend or meddle with hurling of stones, loggats, or quoits, handball, football, club ball, cambuc, cock fighting or other vain games of no value; as the people of the realm, noble and simple, used heretofore to practise the said art in their sports, whence by God’s help came forth honour to the kingdom and advantage to the king in his actions of war, and now the said art is almost wholly disused, and the people indulge in the games aforesaid and other dishonest and unthrifty games, whereby the realm is like to be kept without archers.

The proclamation was followed by a series of similar laws over the next two centuries including statutes from Edward IV, Henry VII, and Henry VIII who, in 1512, clarified that the requirement to practise applied to all men ‘not lame, decrepute or maymed’ under 60 years of age.30

The risk of invasion by the powers of Catholic Europe increased after Henry VIII’s break with Rome, and to guard against such an invasion Henry VIII, in 1538, implemented a programme of military and naval preparations along the southern and eastern coasts from Kent to Cornwall. The French ambassador Marillac reported in 1539 that ‘In Canterbury, and the other towns upon the road [to Dover], I found every English subject in arms who was capable of serving. Boys of seventeen or eighteen have been called out, without exception of place or person . . . Artillery and ammunition pass out incessantly from the Tower [of London], and are dispatched to all points on the coast where a landing is likely to be attempted’.31

In February 1545 Stephen Vaughan, an English merchant and royal agent, reported to Henry VIII that he had heard a rumour of a planned French invasion of England, to start at Margate:32,33

‘A French broker,’ he [Stephen Vaughan] said, ‘hath secretly called upon me. He asked me if there was not in England an island called Sheppy, and a place by it called Margate, and by those two a haven. I said there was. ‘Then,’ said he, ‘you may perceive I have heard of these places, though I have never been there myself. To the effect of my discovery,’ said he, ‘you shall understand that the French King hath sent unto this town of Antwerp a gentleman of Lorrayne named Joseph Chevalier. The same hath sent out of this town, two days past, a Frenchman, being a bourgeois of Antwerp, named John Boden, together with another man that nameth himself to be born in Geneva, but indeed he is a Frenchman. These two,’ he said, ‘were sent from hence in a hoy by sea, and had delivered unto them eleven packs of canvass to be by them uttered and sold in London, and the money coming thereof to maintain their charges there. The said Joseph Chevalier, besides these two, hath sent another broker named John Young, also of this town; he speaketh singularly well the English tongue. These three shall meet together in London, and shall lodge in a Fleming’s house dwelling by the Thames, named Waters. The first two shall have charge to view and consider the said Isle of Sheppy, Margate, and the grounds between them and London; what landing there may be for the French King’s army, what soils to place an army strongly in. For,’ said he, ‘the French King hath bruited that he will send forth this summer three armies, one to land in England, the second in Scotland, and the third he mindeth to send to Boulogne, and Guisnes, and Calais. But his purpose is to send no army to Scotland, for he hath appointed with the Scots that while his armies shall be arrived, the one at Margate and the other at Boulogne, they shall set upon the north parts of England, with all the power they can make. The French King proposeth with his army that he appointeth to land in the Isle of Sheppy and at Margate, to send great store of victuals, which shall be laden in boats of Normandy with flat bottoms, which, together with the galleys, shall then set men on land. This army shall go so strong that it shall be able to give battle, and is minded, if the same may be able, to go through to London, where,’ said he, ‘a little without the same is a hill from which London lyeth all open, and with their ordnance laid from thence they shall beat the town.’

In May 1545 Henry VIII received a report on the defence of the sea coasts of England.34 The report identified a possible landing place for French forces at Margate, ‘between rock and rock, a great quarter of a mile fair landing’, and said that ‘Mr Auchar and the gentlemen of Tenet undertake, with certain artillery and 300 men in garrison, the defence of the Isle’. It was suggested that ‘for the present defence of the said isle to grant the inhabitants 6 or 8 pieces of good ordnance with men practised to handle it, and to command the inhabitants to make a trench in the corner next Canterbury adjoining the Marsh, where they may sustain attacks from the enemy until aid come. The King to appoint three or four gentlemen at any fire given within the isle with three or four hundred men for their succours’.

In 1557, two new Acts were passed, ‘An Act for the having of horse, armour and weapon’ and ‘An Act for the taking of musters’, jointly referred to as the Arms Acts.35,36 The first of these Acts divided the population into ten bands depending on their wealth, and defined what was expected from each of them. At the top of the scale, anyone with an income of £1000 a year or more was expected to provide six horses for men-at-arms carrying the shorter lances used in battle (demi-lance), ten geldings equipped with armour and weapons (light-horse), 40 corslets (suits of armour), 40 almain rivets (studded jackets), 40 pikes, 30 longbows each with a sheaf of arrows (24), 30 skulls or steep caps, 20 bill or halberd, 20 hackbuts (simple firearms), and 20 morions or sallets (helmets). At the bottom of the scale were gentleman, knights and esquires, and substantial yeoman farmers with an annual income between £5 and £10 a year; they were required to supply one coat of plate, one bill or halberd, one bow with arrows, and a steel cap. The second of the Acts concerned the gathering of the military forces, a muster, for training and inspection. The Act was designed to prevent some of the corrupt practises that had developed over past years. As described in the Act ‘a great number hath absented them from the said Musters, which ought to have come to the same, as also for that many of the most able and likely men for that service have been through friendship or rewards, released, forborn and discharged of the said service’. In future, anyone missing a muster without good reason would be imprisoned for ten days and anyone in charge of a muster accepting a bribe would be fined ‘ten times so much as he shall so receive’. A further development came in 1573 when it was ordered that ‘a convenient and sufficient number of the most able’ men at the muster would be selected to be ‘tried, armed and weaponed, and so conveniently taught and trained’ to form an elite band, referred to as the trained band.37 The militia as a whole would be mustered just once a year, or less, but the trained band would meet more often, sometimes as frequently as once a week, for training in the use of their weapons. The records of the militia at Canterbury include a payment of 6s 8d ‘paid to the trayned shott when they went to Margate’, possibly to help with the training there.38 In 1679 the records of the Overseers of the Poor for the parish of St John’s included an item: ‘Paid for clearing Matt. Mummereyes musquett 2s’, which does rather sound like something from an episode of Dad’s Army.39 The muster system was to remain, more of less unchanged, until 1757 when ‘An Act for the better ordering of the Militia Forces in the several counties of that part of Great Britain called England’ was passed, leading to the awarding of ‘Commissions to a proper number of Colonels, Lieutenant Colonels, majors and other Officers . . . to train and discipline the Persons so to be armed and arrayed’.40

The musters were held over two days and became something of a social occasion. They were usually the responsibility of the Lord Lieutenant of the county but for the Cinque Ports the responsible official was the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, who appointed a muster-master to oversee the process. In 1677 Edward Randolph, the muster-master for the Cinque Ports, complained ‘that he has several years’ salary due to him’, totalling £79 5s 10d, calculated ‘according to the rate agreed on in 1617 and paid until 1665’.41

Margate, St Peter’s and Birchington together formed two companies of militia, a ‘select company’ and a ‘general, not selected company’ which were inspected at an annual muster by the Deputy Constable of Dover Castle, acting on behalf of the Lord Warden.16,42 Lewis commented on the considerable cost of these musters, giving as an example the costs involved in 1615 when Thomas May was the Deputy at Margate:16

To the messenger who brought the Warrant to warne the Musters — 1s

More, moneys layed out when Sir Robert Brett took Muster at Mergate the 12 and 13 daies of October for his diet and his followers — £3 18s

More, to Mr Warde — 10s

More, to Mr Packenhum — 10s 8d

More, to --- Dibbe — 5s

More, to the Trumpeter — 5s

To the two Dromers — 5s

To Sir Roberte’s servants

First, to his Chamberlen and Purse bearer — 6s 8d

More, to the serving men — 2s 6d

More, to the Coachman, footman, and horse keepers — 4s 6d

More, to Mr Rawworth, the Clarke of the Musters — 3s 4d

More, to Mr Packenhum’s and Mr Ward’s men — 2s>

More, to the Muster Master — 9s 2d

More, to Mr Raworth for writing and ingrosing of our Muster Role — 6s

To the Ferryman for passing Sir Robert and his company over the haven at Sandwich — 8s 7d

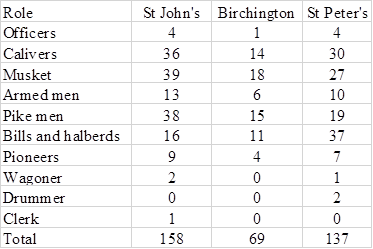

The muster role for the select and general companies of the Isle of Thanet in 1599 shows 364 men in all, of whom about half came from St John’s:43

About half the men carried hand weapons such as pikes and halberds (including those listed simply as ‘armed men’) and half carried fire arms such as calivers and muskets; the lower orders made up the ‘pioneers’, equipped with picks and shovels. The three wagoners were responsible for transport and the two drummers were there to ensure that the soldiers kept pace when marching. Calivers and muskets were precursors to the rifle. The caliver had a barrel between 39 and 44 inches in length, giving the weapon an overall length of about 55 inches; it weighed between 10 and 12 pounds. The musket was much larger and heavier than the caliver, with a barrel between 45 and 55 inches long, and a weight of about 20 pounds; its weight was such that it had to be supported by a forked rest during aiming. The pikemen, who were expected to be ‘the strongest men and best persons’ had to fight at close quarters and so had body protection in the form of a corslet, a metal shell around the body, with pouldrons, vambraces and tassets which were metal plates to protect the shoulders, arms and thighs, and gauntlets. To protect their heads the pikemen wore a steel cap or morion well stuffed for comfort, tied with a scarf under the chin. The halberd was a shorter weapon, some 7 to 8 feet long, with a metal point like the pike for thrusting, a heavy blade for cutting and a hook for dragging horsemen from their saddles.31,44,45 The general company of 1599 was about half the size of the select company, with 76 coming from St John’s.46

The muster role for 1572 for St John’s, St Peter’s and Birchington combined shows 170 men in the select band and 204 in the general band, giving 374 in total, a total figure very similar to that for 1599. The Muster Role for 1619 shows that the Select Company then contained 147 men, including 3 officers and 2 sergeants, and the General Company contained 172 men including 3 officers and 2 sergeants.42,47 In the Select Company 60 were Corsletts, pike men named after their corslets or body armour, and 80 were Musquets, with a clerk and a drummer and two waggons looked after by two wagoners. In the General Company 30 were Corsletts, 76 were Musketts, and 60 were ‘Dry Pykes’ who, it seems, were pike men who wore no armour;48 there was also one drummer. The officers of the Select Company were listed as ‘Paul Cleybrooke, captaine, esquire, Manasses Norwood, Lietenant, gen., and William Cleybrooke, ensigne, gen.’ and those of the General Company were listed as ‘Valentine Pettit, gent., captayne, William Parker, Liuetenauntt, and Thomas Busher, Ensigne.’ Paule Cleybrooke was from Fordwich, Manasses Norwood from Dane Court, William Cleybrooke from Nash Court, Valentine Pettit from Dent de Lyon, and William Parker from Minster, illustrating once again the importance of the large farming families in the Isle of Thanet. Gradually the organization of the trained band became more professional and in 1684 commissions were given to ‘Lieut. Andrew O’Neale to be lieutenant and to Ensign Stephen Greedhurst to be ensign of a company of trained band soldiers of St John’s in the Isle of Thanet . . . in the second regiment of the Cinque Ports’.49

Musters were generally held on some convenient open grround, usually somewhere in the countryside.31 Arthur Rowe made the suggestion that the muster in Margate might, however, have been held in the spot close to the harbour and Fort known as Cold Harbour. This idea was based on the belief that Cold Harbour was a name used throughout the south of England for the mustering place of the trained bands.39 There is, however, little or no evidence for this, and the name Cold Harbour is usually thought to derive either from the name for a refuge for the destitute or from the name given to a station on the line of a Roman road. It seems more likely that the Cold Harbour at Margate got its name simply from being a cold and windy spot close to the harbour and, anyhow, it would be too small an area for holding a muster.

Perhaps because of its membership of the Cinque Ports, the Royal Navy never maintained much of a presence at Margate, although a brass plate in St John’s church records the death in Margate in 1615 of Roger Morris, one of the principal Masters of Attendance of His Majesty’s Navy Royal.85 The Principal Master of Attendance was a rather ill-defined post, but a holder of the post was essentially a local representative of the navy, generally responsible for the naval side of a royal dockyard. What he was doing in Margate is not known; he might have simply retired there or he might have been posted to Margate to look after the interests of the navy. Nevertheless, an extract from a manuscript, The life of Mr Phinear Pette, one of the Master shiprights to King James the first, shows just how useful he could be to any senior navy officers who happened to be in the area:86

1612: The 15th [April], London, we came to an anchor in Margate road; the next day the Lord Admiral went ashore at Margate, and lay there three daysh, at Mr Roger Morris’s, one of the four masters of his majesty’s navy, and then returned aboard. The 21st, the lady Elizabeth, his grace the Palsgrave, and all their train, came to Margate, and were embarked in barges and the ships boats, and were received on-board the admiral, and lay there all night. The 22d the wind getting Easterly, and likely to be foul weather, her highness and the Palsgrave, and most part of her train, were carried ashore to Margate. The 25th they were all brought on-board again.

Press Gangs

The charters establishing the Cinque Ports required them to provide both ships and sailors in time of war, but only for fifteen days a year; although the burden of manning the ships fell largely on coastal communities, the burden was manageable. However, by the eighteenth century naval ships were very much larger, with much larger crews, scattered all over the world for long periods of time. Manning the navy had by then became a problem and relied increasingly on the use of press-gangs.50 The term ‘pressing’ for the procedure is something of a misnomer, as in fact the men were ‘impressed’ or ‘imprested’, the word imprest meaning to pay someone in advance to guarantee their service; in the army this took the form of paying a man ‘the King’s shilling’ so that it could be claimed that they had volunteered to join.

Navy press gangs were meant to operate within clearly defined limits, although as press officers were paid an allowance for each man they recruited these limits must often have been broken.51 The intention was to recruit seamen with few family ties. At sea, pressing was not permitted from outward-bound vessels, and so press gangs would board homeward-bound ships to find their ‘volunteers’ although even then they had to leave enough men on board to enable the ship to reach its destination safely. Press gangs would also target fishing and collier fleets, especially those on the east coast.51 On shore the press gangs were meant to recruit just able-bodied mariners, between the ages of eighteen and sixty and would concentrate on places with large numbers of seamen, such as Wapping and Rotherhithe along the Thames.

Who actually had the authority to impress men within the Cinque Ports became something of a contentious issues in the sixteenth century. The head of the navy in England was the Admiral of England, later to be known as the Lord High Admiral, an office created around 1400. In the sixteenth century the post of Vice-Admiral was also created, with one Vice-Admiral being responsible for each of the maritime counties. The first Vice-Admiral of Kent was Sir John Tregonwell, appointed in 1525.52 The responsibilities of the Vice-Admirals included impressing men for naval service but, based on long custom, it was accepted that ‘the Lord Warden is Admirall within the Ports’, so that within the Cinque Ports it was the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports rather than the Vice-Admiral of Kent who was responsible for pressing men.5 Although the offices of Vice-Admiral of Kent and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports were separate offices, they were occasionally held by the same man, as, for example, by William Brooke, tenth Baron Cobham, who was appointed Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports in 1558 and Vice-Admiral of Kent in 1559.

There are a number of records from the 1560s of payments to press officers for impressing men from Margate and other places in Kent.53 In August 1562 Butolph Moungey was paid £16 13s for 222 mariners ‘by him prested from Folkestone, Hythe, Margate, Lydd, Rye, Winchelsea, Hastings, Newhaven, Brighton, Kingston, Heene, Worthing, Lancing, Old Shoreham, New Shoreham, and in divers places thereabouts in Kent and Sussex’ and for conducting them to Gillingham, ‘at 18d every man’. On July 6 1563 Lancelot Tristram was paid ‘for the conduct of Jeffrey Fraxson, Robert Sutton, John Dowes, Henry Cowper, Thomas Beate, Richard Pissinge and 10 other mariners by him prested from Dover, Kingsdown, Sandwich and thereabouts in Kent to serve in Her Grace’s ships at Chatham, distant 36 miles, at 18d every man — 24s; [and] for the conduct of Thomas Parker, John Bayllie, Thomas Houghe, Christopher Parkins, Thomas Homan, William Tompson, George Browne and 25 other mariners by him prested from Deal, St Lawrence in Thanet, St Peter’s, St John’s [Margate] and thereabouts in Kent to Chatham, distant 24 miles, at 12d every man — 32s.’ On July 10 he was also paid £9 8s 6d ‘for the conduct of John Hatley, William Goodson, John Castell, Thomas Atkynson, Robert Clarke, Thomas Tuckar, Henry Readman and 102 other mariners by him prested from Dover, Folkestone, Hythe, Lydd, Rye and thereabouts to Chatham, distant 36 miles, at 8d every man — £8 3s 6d; and more to him for the conduct of Robert Harrys, Henry Martyn, James Bennet, Richard Hemmynge and 21 other mariners by him prested from St Peter’s, St John’s and divers other places in Thanet in Kent to serve in Her Grace’s ships at Chatham aforesaid appointed to the sea, distant 24 miles, at 12d every man — 25s.’ On the same day he was paid his expenses ‘for the charges of him and his horse, travelling about the presting of 134 mariners out of sundry places in Kent and Sussex to serve in divers Her Grace’s ships appointed to the seas, by the space of 8 days, at 3s 4d per diem — 36s 8d; more for so much by him paid to John Hewson of Dover for his charges and horse-hire riding into Thanet for the like presting of mariners for the said service — l1s 4d; more by him paid for a letter of attendance had from Dover castle — 2s 6d; more paid to William Browne for his charges riding from Dover alongst the coast to Rye with precepts — 4s 6d; and more to him for the hire of post horses from Dover to London, and also for other charges incident to the premises — 10s. Summa — £2 15s’. Tristram’s charges for attending at Dover castle and for taking precepts [a warrant] to Rye suggest that his pressing in the Cinque Ports was done with the agreement of the Lord Warden.

In January 1602 Cobham, as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, was ordered to impress a hundred sailors from the Cinque Ports to keep the fleets manned and help patrol the Irish coasts after the defeat of the Spanish and Irish at Kinsale:54

Her Highness pleasure and commandment is that your Lordship cause a general muster to be taken of all the mariners and seafaring men fit for service within the Portes of your Lordshipps lieutenancie and wardenrye from the age of sixteen to three score years owt of which ther shalbe choice made of one hundred of the most able and sufficient.

Cobham, however, decided that only about half of the men should come from the Cinque Ports with the other half coming from the rest of Kent, as ‘I find the Portes have ben extraordinarily chardged of service for the shippes upon every small occasion’.54 In fact, 57 men were mustered from the Cinque Ports, of whom 6 were from the parish of St John’s, 4 from Ramsgate, 4 from Broadstairs and 7 from Dover. The arrangement for the impressment was somewhat different from that for soldiers, the sailors being given twelve pence for impress money with a half-penny per mile from their home port to Chatham; they were charged ‘uppon payne of death to present themselves before the officers of the navye by the laste daie of the present January to be disposed into soch shippes as shalbe meete.’ The order sent to Cobham included a reminder that many of the drafted men would present themselves ‘unarmed and naked without anie convenyent clothes’. As this was both a danger to themselves and a cause of infection he was to ensure that those that could ‘sholde furnish themselves’ and those without means should be fitted out ‘by their parents, masters or friends with swords and daggers and all necessarie apparell’.54

The convention that the Lord High Admiral had no authority to impress in the Cinque Ports continued into the seventeenth century. When George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham and Lord High Admiral from 1619, wished to impress ‘three score seamen in the Cinque Ports, to man the Victory and Dreadnought’ in 1621 he had to write to Lord Zouch, the Lord Warden, asking him to issue the appropriate order.55 Again in 1623 when the Privy Council and the Commissioners of the Navy wished to issue instructions concerning the impressing of sailors in the Cinque Ports, the instructions had to be addressed to Lord Zouch.56,57 The instructions sent by the Privy Council concerned seamen who ran away:

The punishments will henceforward be heavy against all seamen who run away from their ships, enter foreign service, or endeavour to avoid the prest, particularly as regards the fleet now preparing for Spain; 150 mariners are required from the Cinque Ports; all such as endeavour to escape are to be apprehended, and all abuses of presters, in impressing unfitting persons, or discharging for favour or money those who are fitting, are to be punished. Whitehall, March 9.

The instructions from the Commissioners of the Navy concerned the choice of men to be impressed:

To be observed in the presting of mariners. All seamen are to be summoned to appear, according to lists previously sent in, and efficient men to be chosen with discretion, so as to injure trade as little as possible. With note of the rates to be allowed them.

The Duke of Buckingham, as Lord High Admiral, disliked having no authority to impress in the Cinque Ports, as he explained in 1626:58

The king’s service is much hindered; for the most usual and ordinary rendezvous of the king’s ships being at the Downs, and that being within the jurisdiction of the lord warden; the lord admiral or captains of the king’s ships have no power or warrant to press men from the shore, if the king’s ships be in distress.

Buckingham’s solution to the problem was, in 1624, to purchase the Lord Wardenship of the Cinque Ports from Lord Zouch who was then an old man and no longer wished to hold the position.59 This, for a while, put an end to the clash of interests between the Lord Warden and the Lord Admiral and united the entire naval administration of the country in one man, him.59 The arrangement was, however, short lived and ended with Buckingham’s assassination in 1628; the two offices were only once again to be held by the same man, and that was between 1702 and 1708, by Prince George of Denmark.

The year before his assassination Buckingham had led an expedition to fight against the French at La Rochelle, in support of the Huguenots. As part of his campaign Buckingham had ordered a ‘general muster throughout England of all mariners [and] mid-seamen’ to be held in June 1626.60 Papers in the archives of the Cinque Port of Rye show that this was linked to a ‘strict stay of all ships and vessels going forth’ from any of the Cinque Ports.61 In practise this proved impossible to enforce, much to the annoyance of Buckingham, who addressed a stiff letter to the Mayor and Jurats:61

Whereas I am credibly informed that notwithstanding the strict order and commaund given for a generall restraint of all shipps, barques, and vessells, there doe dayly passe out of your porte or the members thereof aswell sloopes as barkes and other vessells to the infringement of the King’s expresse comaunds and prejudice of his Majesty’s service. Wherefore these are to will and require you not only to inquyre and certifye me what barques or vessells (since the said restraint) have passed out of your porte, and by whose directions, licence, helpe, and meanes, and whether they have gonne, but to take a more strict and vigilant course, that noe shippe, barque, sloope, or other vessell whatsoever of what quallity or condition soever, whether belonging to his Majesty’s subjects or straingers doe by any meanes passe or goe forth of your said porte, roade, or harbor untill further order from me or the Lieutenant of Dovor Castle.

The restrictions on ship movements also applied to Margate and led, in June 1627, to a petition from the inhabitants of Margate asking Buckingham for an exemption: ‘Petition of Inhabitants of Margate, member of the port of Dover, to Buckingham. Pray for removal of the restraint from their trade with small hoys and vessels laden with corn to London’.62 It is not known whether or not Margate got its wish but in 1628 permission was given for hoys from a number of ports, including Margate, to ship corn abroad, as long as it was to ‘his Majestie’s friendes’:63

An order granted to the inhabitants of Feversham, Milton, Rochester, Whytstable and Marget to transport corne into forreigne partes in good amitie with his Majestie by virtue of the generall order of the 27th of February 1627, they first putting in bonde to carry the same to none but to his Majestie’s friendes.

During the reign of Charles II the Admiralty began to impress sailors in the Cinque Ports without bothering to first get permission from the Lord Warden. In 1668 a petition was addressed to James, Duke of York from the Cinque Ports claiming that ‘their liberties since “the late distraccions” have been much impeached and infringed so that many have left the Ports, and the towns are decayed and they therefore place before him their grievances’.64 The petition listed seven specific grievances of which the third read:

The officers of the Admiralty Court often impress seamen without the knowledge of the chief officer of the town and instead of making arrests themselves send warrants to the mayor, bailiffs and jurats with their common officer making them thereby but servants liable to contempt.

By the eighteenth century any rights of the Cinque Ports over the impress of sailors arising from ‘ancient customs and privileges’ were largely ignored.65 An incident in 1702 led to a petition from Deal to Prince George of Denmark, who was both Lord High Admiral of England and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports at the time:

The Humble Petition of the Mayor, Jurats and Commonalty of the free town and Borough of Deal, a member of the Cinque Ports, Sheweth — That great privileges and immunities have been anciently granted to the Cinque Ports for their signal service at sea, which have been confirmed by Magna Charta and preserved to them hitherto.

In grateful acknowledgment whereof they have constantly supplied the kings and queens of this realm with great numbers of able and efficient seamen to serve in the wars at sea. That, by the customs and privileges of the Cinque Ports, all seamen thereunto belonging are to be impressed and raised only by the officers of the Lord Warden within the said ports, or the Mayor and Magistrates of each town thereof, and in this manner great numbers of seamen, whenever it has been required, have been provided by the said ports. That your Petitioners have on all occasions distinguished themselves by their readiness and zeal for Her Majesty’s Service. As an instance thereof, have encouraged and compelled about four hundred seamen to go on board Her Majesty’s ships of war, by the Magistrates of this little town of Deal, who are now actually in the public service, and this hath been the custom of furnishing the Royal Navy from the Cinque Ports, and not otherwise. The impressing of seamen by persons unauthorised by the Lord Warden is not only in opposition to the liberties and privileges of the Cinque Ports, but is frequently attended by disturbances, riots, tumults, and sometimes bloodshed: and it happened so in the town of Deal on the fourth instant, when some strangers, led on by the Marquis of Carmarthen to impress seamen, laid hold of one, Phillips, and thereupon drew their swords and grievously wounded several townsmen, in particular, one of the Magistrates who came to suppress the riot and prevent murder, and also one, Simmons, who came to the assistance of the said Justice, receiving no less than five several wounds; and soon after, the said Marquis of Carmarthen, without any provocation whatever, seriously assaulted the Magistrate by striking him in the face, in the execution of his office, which had well nigh produced considerable disturbance. The energy and zeal of the Magistrates succeeded at last in preserving the peace, so that, in return for the assault, the marquis nor his party received any injury; but the marquis and his followers persisted in this irregular and unreasonable way of impressment, and, therefore to prevent further mischief the Mayor was compelled to raise a strong watch to keep the peace to the great charge of your Petitioners. That unless seamen in Deal are impressed in conformity to the ancient customs and privileges of the Cinque Ports and by the officers only appointed by the Lord Warden, or by the Justices of the town of Deal (who best know who are fit to serve), it will be difficult to maintain order and preserve the peace within the said town of Deal for the time to come — for your Petitioners have been in danger of their lives continually. Wherefore your Petitioners humbly pray your Highness will be pleased to redress the affronts done to the Magistrates and inhabitants in endeavouring to preserve Her Majesty’s peace, and graciously to consider of this matter and to give suitable directions thereon as your Royal Highness shall think fit, whereby your Petitioners may enjoy their ancient privileges and lie safe in their lives and estates, and not exposed to the affronts and insults of strange Impress Masters not residing within the said port of Deal.

And your Petitioners will ever pray.

Witness our Seal of Corporation, the eleventh September, 1702.

The response to the petition was an order by the Queen in Council, dated, 27th September, 1702:65

Upon reading this day the memorial forwarded to His Royal Highness from the Mayor, Jurats, and Common Council of the Borough of Deal, complaining of divers irregularities committed on the inhabitants of Deal in impressing of seamen for the Royal Navy, contrary to the rights and privileges of the Cinque Ports, by the Marquis of Carmarthen, — it is this day ordered by Her Majesty in Council, that a copy of the said memorial be transmitted to the marquis who has appointed the second Council day in November for hearing the complaint aforesaid, of which all parties concerned are to take notice to govern themselves accordingly.

That seems to be where the matter was left. As the author of a later history of the town of Deal complained:66

This was a somewhat equivocal manner of appeasing the indignation of the Deal folk at the decided violation of their liberties. But later on in the century the rights of self-selection for service were entirely disregarded, and Deal became one of the most frequent haunts of the press-gang.

Dover’s response to a similar incident was more robust. In 1743 when the lieutenant of the Devonshire impressed six men in Dover ‘many people of Dover, in company with the Mayor thereof, assembled themselves together and would not permit the lieutenant to bring them away’.50 This angered the Admiralty Commissioners who ordered a Captain Dent of the Shrewsbury to send a press-gang ashore at Dover and press the first six able-bodied seamen they saw, as long as they were bachelors and not householders.50 In this way it was finally made clear that the Cinque Ports had lost any immunity they might once have had against the press-gangs; it is known that a press-gang was active in Margate in 1803.67,68

Wars with Spain

Margate was threatened on several occasions during the wars with Spain in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, particularly during the Spanish Armada scare that started in 1587.69 The Spanish plan was for a two-pronged attack by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, the Commander of the Armada fleet, with some 16,000 Spanish infantry, and the Prince of Parma with some 30,000 men, who were to cross the Channel from the Netherlands. The plan was described in detail in a letter from the King of Spain to the Prince of Parma.70 The first step was for the Duke of Medina Sidonia to ‘sail up the channel and anchor off Margate point’ and then land his troops to establish a beach head at Margate. The instructions given to the Prince of Parma were: ‘when you see the passage assured by the arrival of the fleet at Margate, or at the mouth of the Thames’ you are to ‘immediately cross with the whole army in the boats which you will have ready’. The plan was for the two men to ‘cooperate, the one on land and the other afloat, and with the help of God [you] will carry the main business through successfully’. The King emphasised the importance of taking Margate: ‘the fact of his [the Duke of Medina Sidonia] having taken possession of that port [Margate] will cut the communication of the enemy, and prevent them from concentrating their forces to some extent.’

In 1587 all the maritime counties were told to ensure that their forces were ready to repel any invasion by the Spanish.71 Six thousand men were assembled in a camp at Sandwich, with a camp at Northbourne to watch the coast between Deal and Ramsgate.72,73The Isle of Thanet was recognized as one of five ‘dangerous places’ in Kent ‘fittest to be putt in defence to hinder th’enemye’.71 Edward Wotton was put in charge of the troops in Thanet with Captains Crispe and Partridge in charge of two companies of 250 and 200 trained men, respectively, and Captains Charles Hales and John Finch in charge of two companies of 120 and 150 untrained men, amounting to 720 men in all.71 Martial activity slackened off in the spring of 1587 when it became clear that the dispatch of the Armada had been delayed, but then built up again in the autumn with the expectation of an attack the following spring. An order had been given to keep all ships in harbour but at the end of August 1587 this order was relaxed for fishing boats: ‘Lord Cobham to geve order for the releasing of shippes and barkes belonging to fishermen which were taken at the last Generall Restraint of all shippes, &c,at Sandwich, Dover and Hith, &c’.74 It seems that some ‘gentlemen’ had taken the opportunity of this lull to leave the island, but they were now ordered back: ‘[Lord Cobham] to give commaundment to such gentlemen as did withdraw themselves from the Isle of Thennet, where they inhabited before, to returne againe to their houses in the said Isle for the better strength of the same’.74

On June 18 1588 the Privy Council wrote to Lord Cobham ‘being advertised that the kinge of Spaine’s navie is alreadie abroade on the Seas and gone to the coast of Biscaye’71 On June 27 Sir John Norrys was sent to inspect the defences on the Isle of Thanet and the Isle of Sheppy, another possible landing place for the Spanish:75

A letter to the Deputy Lieutenantes of Kent; her Majestie having receaved speciall advertizment that the Duke of Parma had intent and purpose to attempt the landinge of his forces about the Isle of Tennet or Sheppy, and so to take those Isles to serve for further invacion, because her Highnes did consider the neernes of that coast to the Dukes forces, and the weaknes that the same was in as yet for to make defence, her Majestic sent Sir John Norrys, knight, to take the viewe of those Isles and the coast neere adjoyninge, and other places there of danger, that he might consider what should be meet to be donn for the resystaunce and repulse of the ennemy yf he should goe about to invade those partes and to lande his forces there; therefore they were required that they would accompany the said Sir John Norrys in this service with soche of the Justices of the Peace as inhabyted those partes, and meet with him at soche places as he should appoint, that they might take the viewe of those places together and enforme him what had allready ben donn by them, or in performance of those orders their Lordships sent them in that hehalfe, and to see soche thinges performed and executed as he should thincke meet to be donn for the better strength[en]inge of those Isles and other places subject to the landinge of forraine forces.

In the event the Armada was, of course, defeated by the English fleet led by the Lord High Admiral, Lord Howard of Effingham, with Sir Francis Drake as second in command. The battered Armada fled, with Howard and Drake in pursuit, as far north as the Firth of Forth. The English fleet returned to anchor in Margate Roads but there a violent sickness broke out in the fleet, probably related to typhus or gaol fever. Howard did what he could for his sick mariners. Howard did what he could for his sick mariners and on August 9 1588 wrote to Sir Francis Walsingham that ‘Col. Morgan is at Margate with 800 soldiers: victuals must be provided for them’.76 The following day, in a letter to William Cecil, Lord Burghley, Elizabeth I’s premier councillor, he explained that he could not find adequate accommodation for the mariners in Margate and so was obliged to lodge them in barns and outhouses:77

August 10 1588 — Howard to Burghley.

My good Lord: — Sickness and mortality begins wonderfully to grow amongst us; and it is a most pitiful sight to see, here at Margate, how the men, having no place to receive them into here, die in the streets. I am driven myself, of force, to come a-land, to see them bestowed in some lodging; and the best I can get is barns and such outhouses; and the relief is small that I can provide for them here. It would grieve any man’s heart to see them that have served so valiantly to die so miserably.

He adds in his letter that ‘the Elizabeth Jonas had lost half her crew’ and that ‘of all the men brought out by Sir Ric. Townsend he has but one left alive.’ He goes on to propose ‘that £1,000 worth of new clothing should be sent to the fleet, as the men were in great want’.78 On August 22 he wrote:79

The infection in the fleet is so great that many of the ships have hardly men enough to weigh their anchors. Lord Tho. Howard, Lord Sheffield, and other ships at Margate are so weakly manned that they could not come round to Dover. Recommends that the fleet should be separated into two divisions, the one to remain in the Downs and the other at Margate so as to let the men go ashore. The men are discontented that they have not received their full pay.

Defence of the southern coast remained a worry for many years. In 1596 Elizabeth I sent a letter to Lord Cobham, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, asking for a careful check on the state of preparedness of the coast for any attack:80

The Queen to Lord Cobham. Although we have long had proof of your faithful service, as Lieutenant of Kent, and Warden of the Cinque Ports, by your continual directions to your deputy lieutenants, and your lieutenant of Dover Castle, for mustering, furnishing, and training horse and foot thought convenient to be put in order for service of the country, yet upon considering the present state of affairs, and for the strengthening the maritime counties, you are immediately to repair along the sea coast, view all the forts, castles, and port towns, and see that they are properly furnished with officers, soldiers, ordnance, and ammunition. We have given warrant to the officers of ordnance to supply the defects in the latter . . . You are also to view the state of the port towns, havens, creeks, and passages; to consider as to their strength, and what number of able people they have to serve for their defence, and to cause them to be armed and furnished, at the common charge of the inhabitants; if in a conference with the officers of the towns, you shall find any opportunity to make them stronger against all attempts, either by building sconces, intrenching, or by reparations of the walls or otherwise, you are to procure the inhabitants to yield some contribution towards the charges. Also there should be a number of men, under able conductors, always in readiness to repair to the towns, forts, and castles, for their defence, upon warning by beacons or otherwise.

The previous day Lord Cobham had received a letter from the Privy Council concerning the Isle of Thanet, ‘for the surveye whereof your Lordship is to take order that it may be knowen what defence the inhabitantes are hable to make, and what the whole state of the said Isle is in respect either of offence to be receaved or resistance to be made, and that the inhabitantes may be mooved to be at some charge for the strengthning of themselves with making some sconces or entrenchinges or such like meanes’.81

In January 1599 England had armies deployed in both the Low Countries and Ireland as part of the Nine Years War of 1594-1603 between England and a force of Gaelic Irish chieftains supported by Spain. On January 10, 800 soldiers were to be shipped from Margate, most probably to the Low Countries, but, unfortunately, the expected transport failed to arrive from London:82

A letter to the Maiour and officers of the port of Margett. Whereas the number of 800 soldiers leavied in the counties of Kent and Sussex have bin appoynted to be in readines for their emkarquing at the port of Margett by the 10 day of this instant, who as we understand came thither at the tyme appointed and have attended for shippinge which should have comme thither from London before this tyme, as it was purposed, to take in the saide souldiers at that port and therefore it was supposed it should be needeles to take order for the lodginge and victualinge of them for the tyme there. Now for as much as the stay of the shippinge at London beyonde the tyme prescribed is the cause of the attendaunce of the souldiers at that port of Margett, we doe pray and require you in the meane while till the shippinge shall come downe thither to take order for the lodginge and victualinge of the saide number of souldiers at reasonable rates in the towne of Margett or neere thereaboutes, so as it exceede not the rate of eight pence the day for a man, the chardges whereof we will cause to be repaide and satisfied uppon your certificate to be sent up unto us.

Also in 1599 a letter from the Privy Council to Lord Cobham reported that the King of Spain was expected to attack London and that to do so he would ‘attempt to land his forces either in the Downes or at Margett.’ Cobham was to ‘consider where and how some provision may be made, by casting up trenches or any other way [of] impeachment, at their [the Spanish] likest landing places, either in the Downs or at Margett, which may serve also for defence of those forces which shall be used against them’.83 In 1628, at the start of the reign of Charles I, when a treaty was signed between France and Spain for the invasion of England, moves were again made to protect the Isle of Thanet by moving troops into the Island. About 35 soldiers were billeted in Margate from January 1628 for between 4 and 7 weeks.84 Fifteen of the soldiers were billeted in three ‘victualing houses’, those of Simon Evans, John Pritchard and Ralph Tebbs. The other twenty soldiers were billeted in the private houses of the more important of the local inhabitants.

The Fort

A little above this Town of Mergate, to the Northward on the Cliff is a small piece of ground called the Fort, which has been a long time put to that Use, and was formerly maintained by the Deputies here, at the charge of the Parish. A large and deep ditch is on the land Side of it next the Town, which used to be scoured and kept clean of Weeds and rubbish. At the entrance into it, towards the East was a strong gate which was kept lock’d, to preserve the Ordnance, Arms, and Ammunition here.16

The Fort was paid for out of an assess (tax) allowed each year to the Margate Deputy ‘to bear the charges he was at, in the execution of his office’; the costs of the annual muster were also paid for out of this assess.16Lewis reported that the assess was discontinued in about 1703, which, said Lewis, ‘is like to prove of no service to the place, tho’ they who see not afar off, are well pleased with its being drop’d as saving them a little present money’.

The Fort seems to have been built sometime in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. In 1569 the Spanish Ambassador, Guerau de Spes, reported to the King of Spain that the English ‘are making plans to fortify Margate’, so that any existing fortifications at Margate were likely to have been fairly primitive.87 In a second report, in 1570, he described how Charles Howard had arrived in Margate to take charge of a squadron of ships that, as a mark of friendship, was to accompany a fleet of Spanish ships during its passage through the English Channel, carrying Ann of Austria to Spain for her marriage to the Philip, King of Spain. He reported that Charles Howard ‘has his look-out on the hill close to Margate, and when our Queen’s fleet is sighted they will go out to salute and receive her’.88 The ‘hill’ is presumably the hill overlooking the harbour on which the Fort was to be built, and the reference to just a hill again suggests the absence of any extensive fortifications at the time. In 1588 the Venetian Ambassador in France wrote in a report to the Doge in Venice that ‘there is a scheme for fortifying all the coast on both sides of Margate, which is the place where a landing might most easily be effected, and where it was discovered that the Spaniards actually intended to land. This can be done at very small cost, and in a very short time’.89

The first defences to be constructed at Margate would have consisted of little more than simple earthworks on which to mount guns. In March 1558 steps had been taken to provide Margate with some ordinance:90

A lettre to Sir Richard Sowthewell, Master of thordinance, to geve order that for the better defence of thisle of Thannett in Kent there may be sent furthewith unto Sir Henry Crispe, knight, thies parcelles of ordynance and munycion following; viz.. thre pieces of ordinance called sacres of yron, three fawcons either of yron or bras, foure demibarrelles of powlder, and for every piece xxti [twenty] shott; indenting nevertheless, with the saide Sir Henry for the redelyvery of the same pieces hereafter to the Quenenes (sic) Majesties use.

Sacres (or sakers) and fawcons were field guns designed to be moved from place to place, sacres using five pound balls and fawcons two pound balls.91 It is likely that the six guns were mounted on small platforms on the hill overlooking the harbour. A comment contained in a petition dating from September 1625 suggests that earthworks had been constructed on the hill at about this time.92 The petition, from the inhabitants of the parishes of St John’s and St Peter’s and addressed to George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham and the King’s chief minister, asked ‘that the sconce of fortification erected there in the time of Queen Elizabeth, but then much ruinated, may be repaired’. A sconce was a small protective fortification, such as an earthwork often placed on a mound as a defensive work for artillery, and was much used from the late Middle Ages until the 19th century.

In October 1625 the Privy Council wrote to the Earl of Montgomery, Lord Lieutenant for Kent, agreeing to improvements in the defences of the Cinque Port in general, and of Margate in particular:93