|

Margate before Sea bathing: 1300 to 1736

Anthony Lee

Chapter 1: The Town

|

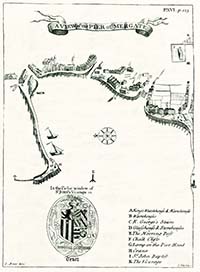

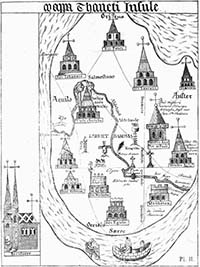

Figure 9. Margate in 1736, from John Lewis 'The History and antiquities as well ecclesiastical as civil, of the Isle of Tenet, in Kent', 2nd ed., 1736. |

We are lucky to have a good description of Margate in 1723 in the first edition of John Lewis’s The history and antiquities ecclesiastical and civil, of the Isle of Tenet, in Kent,1 and, in the second edition of 1736,2 a sketch map of the town (Figure 9) The map shows the harbour protected by a single curved pier designed to exclude winds and waves from the most dangerous direction, the north-east.3 The Pier was a simple box-like structure consisting of wooden piles, packed with anything available, including chalk, soil, flint, and sand;4 a stone structure would have been better able to withstand the winter storms, but there was no local source of stone. The harbour was dry at low water, and had to be entered with care at all times, as a long ledge of rock ran out from the West Cliff across the harbour mouth.3 Lewis described it as ‘a small harbor for ships of no great burden, and for fishing craft’.1 The story of the Pier is told in Chapter 2.

To the north of the harbour, and overlooking it, was the Fort. This was a simple earthwork with platforms for guns, with a watch-house ‘in which men watched with the Parish’s Arms, provided for that purpose’.1 The Fort, says John Lewis, was ‘not only a safeguard to the town, but a great means of preserving merchants ships, going round the North Foreland into the Downes, from the enemies privateers, which often lurk there about to snap up ships sailing that way, which cannot see them behind the land’.1 The Fort was later to become a popular place for visitors to meet and promenade, and is remembered in the name of the present Fort Hill. The history of the Fort is described in Chapter 6.

About half a mile from the harbour was the church of St John the Baptist. The church was first a chapel and then a dependency of St Mary’s Minster in Thanet.5 A chronicle compiled by Thorne, a monk of St Augustine’s Abbey in about 1380 records that in 1124 St Mary’s Minster and its chapels, including that of St John’s, were all assigned for the upkeep of St Augustine’s. The assignment was confirmed in 1182 and in 1237 St John’s acquired a perpetual chaplain. The Archdeacon’s visitations to St John’s in the sixteenth century record that the church was in a very poor state of repair at that time, the chancel without a proper roof and the vicarage in ruins (Chapter 5).7 Gradually, though, things improved and in 1769 the Church was described as:6

a large building of flints rough-cast, with the quoins, windows and door-cases of hewn stone. It has three isles, three chancels, and in the times of popery, there were three altars dedicated to St Anne, St John, and St George, and over them in niches stood the images of those saints. At the west end of the north isle stands the tower, which is square and low, with only a short spire on the top of it; and within this tower is a ring of five bells, the largest in the Island. Adjoining to the south side of the church yard, anciently stood two houses called the Wax-houses, where were made the wax lights used in the church, and at processions. The wax-houses burnt down in 1641.

In the fifteenth century a treasury was built on the north side of the church, ‘a square building of hewn stone with battlements, and a flat roof covered with lead’.1,5 At first this was used for the safe keeping of the church treasures but then became a general store-house for ‘gun-powder, shot, match, &c. for the use of the Fort’.1 In 1701 it was converted into a vestry, ‘and a chimney built’, presumably to keep those using the vestry warm in winter;1 the vestry was used to hold parish meetings and administer poor relief. The west end of the south aisle of the church was partitioned off and used as a schoolroom, probably in the sixteenth century.5

Lewis’s sketch map of Margate of 1736 shows how the town had developed around the bay (Figure 9). On the left of the map are the pier, the King’s Warehouse, and the other warehouses. To the right (marked C on the map) are King George’s Stairs, shown close to Horn Corner on Edmunds map of 1821, at the west end of what was to become the Marine Parade. Roughly midway between the landward end of the Pier and King George’s Stairs is an inlet corresponding to the remains of the old creek; by the time of Edmund’s map this had become Bridge Street, leading into King Street. Immediately to the west of King George’s stairs another inlet corresponds to the seaward end of the future Market Street. To the west of the inlet a road runs west a short way along the bay before turning inland and up the hill to the Church, corresponding to the present High Street. On the extreme right of the map, the ‘Glasshouse and Storehouses’ (D) probably correspond to a location west of the Brooks, around the position of Buenos Ayres in Edmund’s map. The Glasshouse is described in an advertisement from 1723: ‘There is now erecting in the Isle of Thanet a large Glass-house, with convenient store or warehouses for carrying on the Glass Trade, and the gentlemen concerned, propose, from the situation, to carry it on with less expense than attends those built about this City [London]’. 8 This scant information is all we have about the glass-house. It is not certain why it was felt that Margate was a suitable place for the glass trade but the key factor could have been the ready availability of kelp ash used in the manufacture of glass and produced by the burning of kelp (sea weed). The production of kelp ash for the glass industry was continued in Margate until the 19th century, in Alkali Row.9

|

Figure 10. The wooden jetties protecting the shore line. Detail from Lewis’s map of Margate, 1736. |

|

Figure 11. A view from the Pier at Margate. Watercolour by George Keate, 1779. The watercolour shows the crude wooden jetties along the shore line protecting the town from the sea. |

The larger of the Margate inns were concentrated close to the harbour, on what was to become the Parade and Bankside and, indeed, the largest of the buildings shown on Lewis’s map of the town are in this area. Unfortunately the early Parade was not a very attractive place, as made clear in the quotation already given from George Carry’s guide book of 1799.10 Lewis’s map (Figure 10) shows the simple piles of timber, the jetties, lining the shore and protecting the town from the sea; these jetties are also shown in early watercolours of the town such as that shown in Figure 11, dating from 1779. These jetties were frequently damaged by winter storms. For example, in 1691 the inhabitants of Margate petitioned parliament asking for financial help as ‘on the 10th and 13th days of October and the 8th of December last [1690], by the violent blowing of the north-west wind . . . that part of the town which is guarded by the pier and jetties, is so laid open that it is expected to be washed away if the wind should blow fresh at north-west’.11

|

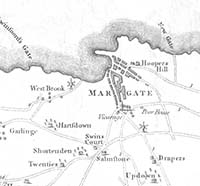

Figure 12. Detail from J. Hall’s map of the Isle of Thanet of 1777 showing the roads to Margate |

Two of the roads leading towards the harbour were referred to as the King’s Highway. One led from the Church to the harbour, and eventually became known as the High Street, a name first used in print in 1766, in an advertisement in a London newspaper for a property ‘situated at the upper end of High-street, near the Church in Margate’.12 The other King’s Highway, leading to the east end of the future Parade, was later known as King Street. Traffic going to and from Canterbury entered the Isle of Thanet at Sarre, and then, according to the season of the year, took either the summer or the winter road, the latter joining the former above Monkton, then passing through Acol, Hengrove, Twenties, Shottendane and Salmestone to join the first King’s Highway. In Harris’s map of 1717 (Figure 8) the junction between the road from Canterbury and the King’s Highway is at a point roughly half way between the harbour and the Church. However, in Hall’s map of 1777 (Figure 12) the road from Canterbury joins the King’s Highway at a point opposite the Church. It may be that the local roads were realigned at some period between the publication of these two maps to meet the needs of the holiday trade.

The King’s Highway leading from the Church to the harbour was narrow and winding. In A description of the Isle of Thanet published in 1765 the ‘Principal street’, as it was referred to, was described as being ‘built on an easy descent, by which means the upper part is clean and dry, but the lower end much otherwise’.13 Zechariah Cozens, in his Tour through the Isle of Thanet, published in 1793, says of the High-street that it was originally ‘but a long dirty lane, consisting chiefly of malt-houses, herring-hangs, and the poor little cottages of fishermen’.14 Malt-houses were buildings in which cereal grain, particularly barley, was converted into malt by soaking the grain in water, allowing it to sprout, and then drying it to stop further growth; the malt was used in brewing, and was either used locally or exported to London by hoy. A herring hang was a shed where the local herring catch was dried and smoked to preserve it. Malthouses and herring-hangs were important for the economy of Margate,1 but would hardly have added to the attractions of this, the principal road into Margate. As late as 1799 George Seville Carey was reporting in his The Balnea, an impartial description of all the popular Watering Places in England, that ‘there is no proper inlet to the town of Margate from any direction whatever; and what they call High-street is a close contracted thoroughfare; many parts of it filthy, with scarcely a decent habitation, and only serves in the present instance to show us what their now-flourishing town was in its original state. The street is too narrow for one carriage to pass another in the day, but in the night it is dangerous indeed!’10

The early history of the High Street is closely linked to the story of the Norwoods, a local family of prosperous yeomen with a long history described in detail in Peter Hill’s book Dane Court, St Peter’s in Thanet; what follows is taken largely from that book.15 In the parish of St John’s was the manor of Dene which, in the seventeenth century, was owned by the Norwood family; the Norwoods also owned Dane Court, a property in the parish of St Peter’s, not to be confused with the manor of Dene. The story of the Norwood family in Thanet starts with Richard Norwood who bought Dane Court in about 1520. On the death of Richard Norwood, Dane Court passed to his son Alexander who died in 1558. Alexander Norwood was described in a document of 1551 as ‘Baylif of Margate’ and another Norwood, William Norwood, was similarly described as being ‘portreeve of Margate’ in the sixteenth century.16,17 The exact meanings of the terms baylif and portreeve vary with time and place but generally a port-reeve is the bailiff of a port town and a port-reeve is the same as a Port warden,18 a position known in Margate as a Pier warden, a position of some authority and importance in the town.

In his will dated 1 January 1558 Alexander Norwood specified that at the time of his burial, ‘there be dispended and layde out . . . in the service of God, and to poore people’ the sum of 40 shillings. There was a further 40 shillings for similar purposes, and within one month of his death £20 was to be distributed to the poor of St John’s and St Peter’s ‘and in other deades of charitie, where moste neade shalbee’: in addition, he gave to ‘the poor of Margate all that mony that I have bestowed and layde out all redye’. His bequests included one to his son Valentine of ‘all such store of come [corn?], cattal and other thinges’ at Lucks Danec [Lucas Dane] in St John’s ‘where I dwell’. The main properties described in the will were the house and lands known as Lucks Dane, the Court House and barn with 20 acres of land also , leased to his son Alexander II, and Dane Court and a windmill in St Peter’s. Lucks Dane went to his wife Joan and, after her death, descended to Alexander II who also inherited Dane Court. The location of the Court House is unknown.

Alexander II married Joan, nee Kempe, the widow of Roger Howlett of Margate, and all their children were baptised at St John’s; at the time of his death in 1583 he was living at Lucks Dane. Alexander II and his wife Joan had three daughters and three sons who survived childhood. In his will Alexander II left to his wife Joan two annuities of £10 each, one ‘issuinge and goinge out of my mansion house wherein I now inhabite [Lucks Dane] and out of all the landes thereunto belonginge’ and the other ‘out of my messuage and farme called Dane Court’. His properties included, in addition to Lucks Dane and Dane Court, ‘my house at Margate called the Corte House, and my little house in the occupation of Peter Dalient and two parcells of arrable lande conjoyninge, by estimation six acres, lienge and beinge not far from the said little house’, and a mill and land at St Peter’s. These properties were to be used by his wife for seven years and then to go to his three sons, Lucks Dane to his son Joseph, Dane Court to his son Manasses, and his remaining property to his son Alexander III.

Manasses Norwood was responsible for a considerable expansion of the property owned by the Norwoods in Thanet, purchasing the manor of Dene, together with the Hengrove estate in the parish of St John’s; the manor of Dene had passed into the hands of the Crown on the dissolution of the monasteries, and had then been granted by James I to William Salter who sold it to Manasses Norwood. On Manasses Norwood’s death in 1637 most of his land went to his son Richard and Richard, on his death in 1644, left most of his property to his three sons Alexander, the eldest, William, the middle son, and Paul, the youngest, although some land was to be sold for his daughter, this being ‘lands lying on the east side of ye way leading from Church-hill to Margate’.19 His will also included a small bequest of £10 a year to his ‘good friend . . . Daniel Gibbons, gent’ to be paid for from the windmill and lands in St John’s.15 Harris’s map of Thanet (Figure 8) shows three windmills in Margate, one behind the Church, in what later became Mill Lane, one on rising ground S. S. W. of Nash Court and known as Humber’s Mill, and one between Dandelion and Birchington, close to Quex. The map of Kent published by Symonson in 1596 shows just two of these three mills, Humber’s Mill and the Mill near Quex.20,21 The earliest known reference to a mill in the parish of St John’s is in the report of the annual visitation of the Archdeacon of Canterbury to the parish in 1581, when Thomas Deale was reported ‘for being absent from Common Prayer on the Sabbath Day, and for grinding with his wind mill’:7 presumably this corresponds to one of the two mills on Symonson’s 1596 map. Humber’s Mill burnt down in 1732:22 ‘On Thursday the 16th past between nine and ten o’clock at night a fire broke out by an accident unknown in the windmill of the widow Pannell, commonly call’d Humber’s Mill, in the Parish of St John Baptist in the Isle of Thanet, which in less than an hour’s time burnt down the said mill, to the great impoverishment of the two poor families who had their dependence on it.’ It is likely that the windmill referred to in Richard Norwood’s will of 1644 was the Mill Lane Mill.

The break up of the estate put together by Manasses Norwood proved to be the beginning of the end of the Norwoods’ influence in Thanet. Alexander Norwood received, amongst other land, the manor of Dene, Nash Court, and other lands in St John’s. It seems that Alexander ran up debts; he died before his mother and his mother’s will records that he died owing her money. During his life he mortgaged the manor of Dene and part of the demesne lands (demesne land is land, not necessarily contiguous with a manor house, but retained by the owner of the manor for his own use). Alexander’s widow was living in Nash Court when she died in 1706, and Nash Court was sold to David Turner, a yeoman of St John’s.

The exact location of the demesne land belonging to the manor of Dene is not known; Lewis reports that it amounted to 203 acres.2 However, Lewis’s description of the Vicarage land and the glebe land belonging to it provides some clues. Lewis says: ‘the site of the Vicarage, with the dove-house, garden, containing one acre and three rods more or less, doth lie to the tenement of Edward Toddye and the land of John Goodwin East; to the church-yard and Deanery land in the tenure of Christopher Hayes West; to the common street and Church yard and tenement of the same Edward Toddy North; and to the King’s Highway South’. Of the glebe land he says: ‘one parcel of land containing four acres and one rod more or less doth lye at a place called the Vicars Cross, to Deanrye land, and the lands of Michael Allen east; to the King’s Highway West; to Deanrie lands and the lands of the said John Goodwin North; and to Deanrie lands South’.2 The Deanery (or Deanrie or Deanrye) land referred to here is land formerly belonging to the Manor of Dene, and Lewis’s description shows that this included much land in the vicinity of the Church and the King’s Highway.

The district around the Church was referred to as Cherchedowne and then as Church Hill. The reference to Cherchedowne occurs in a deed dating to 1444:23

William Crawe of the parish of St John, Isle of Thanet, grants to John Gotle, esq., of the same 5 roods lying at Cherchedowne between the land of the lord vicar of the parish of St John on the E. and the land of the Church of St John on the W. and the common way on the S. and N.

Warranty. Witnesses: John Cowharde, William Sprakelyng, John Lucas, Thomas Lyon, John Crosse and others.

The reference to the ‘common way on the S. and N.’ probably puts Churchedowne between the roads from Margate to St Peters, to the north, and to Ramsgate, to the south. Later the area around the Church was referred to in deeds and parish records as Church Hill. This included the upper end of the present High Street and the whole of the plateau on which the Church stood, including Frog Hill (now Grosvenor Gardens), the church-ward ends of Long Mill Lane (now Victoria Road) and Ramsgate Road and the old Church Field.24 The King’s Highway leading from Church Hill to the harbour ran for most of its length through farm land, and the settlements around the Church and around the harbour were originally quite distinct. This is reflected in the description in Richard Norwood’s will of 1644 quoted above of ‘lands lying on the east side of ye way leading from Church-hill to Margate’; at this time Margate was used as a term for just the area around the harbour.19

When the Norwoods came to sell their land in St John’s, they did so in a piecemeal fashion, selling off small quantities of land to individual purchasers, resulting in an interesting hotchpotch that survives to this day. In 1643 Richard Norwood sold 10 perches of land at Church Hill, adjacent to the King’s highway, to Edward Poole, ‘butcher of the parish of St John’, and in 1647 Alexander Norwood sold him a further 10 perches of land, adjacent to the first.19 Two years later, in 1649, Edward Poole, now described as a bricklayer, bought from Alexander Norwood ‘his two messuages situated at or near a place commonly called by the name of Church-Hill, yielding one shilling a year at feast of St Michael the Archangel’.19 In his 1661 will Edward Poole left to his son John Poole ‘all that messuage, and one piece of land, situated at a place called Church-hill, with the Lyme Killne adjoining’.19

In 1647 Robert Todd, a mariner of St John’s parish, gave Alexander Norwood £4 for:25

one piece or parcel of land containing by estimation 8 perches, lying and being in the said parish of St John Baptist, abutting to the lands of Edward Poole there towards the north, to the demesne land of the Manor of Deane there towards the east and south, and to the King’s highway there towards the west. To have and to hold the said piece or parcel of land with the appurtenances unto the said Robert Todd, his executors, administrators and assignes from the day of the date of these presents for and during the full end and term of one thousand years from thence next ensuing fully to be complete and ended, yielding and paying therefore yearly during the said term unto the said Alexander Norwood the sum of twelve pence of lawful English money, at the feast of St Michael the Archangel in every year of the said tenure.

This land was then bought by Matthew Silk, a bricklayer, who, at some time before his death in 1729, built ‘a messuage and kitchen’ on part of the land, the kitchen presumably being a separate building. The property was advertised for letting in 1733:26

Now to be let

A lime kiln and a very good convenient Whiting-House and well supplied with fresh water. ¼ acre of land adjoining to it, and a very good Dwelling House in Margate in the Isle of Thanet, late in the occupation of Mr Matthew Silk, deceased. Inquire of Mr Robert Wells or of William Simmons, of Margate.

NB. All customers may be supplied with Whiting at the Whiting-house as usual.

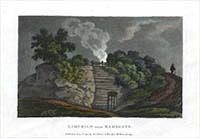

In 1769 the site still contained ‘one whiting shed and lime kiln’ and ‘a garden, containing one rod, lying and being on the Wind Mill Green’; Wind Mill Green was a reference to the location of the old Mill Lane Mill located behind the Church in Harris’s map (Figure 8), on what was to become Mill Lane.25 By 1876 the original house had been converted into two, being numbers 123 and 125 High Street; they can be seen on modern maps of Margate on the East side of the High Street just below the junction with Mill Lane, close to the Saracen’s Head.25 The presence of a lime kiln on the land of a bricklayer and builder such as Matthew Silk was not surprising, builders using the kilns to prepare lime for mortar. Arthur Rowe reported that, in 1801, there were three lime-kilns in nearby Church street, all belonging to builders.24 Such lime kilns were a major source of air pollution in many towns.27 There are no known pictures of lime kilns in Margate, but Figure 13 shows a picture of a lime kiln at Ramsgate, half concealed, but issuing rolling volumes of smoke.

|

Figure 13. A lime kiln near Ramsgate, 1800 |

Early deeds for properties on the north side of Mill Lane tell us more about this part of Margate.28 The first, from 1681, records a conveyance from John Smith, a chirurgeon (doctor) of Margate, to John Prince of Margate, a famous local brewer of ale, of two acres of arable land ‘abutting to the Church way leading from Margate east to the way leading to the mill there from the street south, to the lands of John Smith north, to the lands of Matthew Smith and Nicholas Laming west’; ‘the way leading to the mill’ became Mill Lane and the ‘street’ became the High Street. The land then passed from John Prince to his son Thomas, and then to his son Richard, whose widow Mary sold it to Matthew Smith, a Margate butcher, in 1730, for £100.

It is not known when the Mill behind the church was built. The mill mentioned in Richard Norwood’s will of 1644 was probably Mill Lane Mill and an indenture of 1693 records the purchase of ‘Margate Mill’ by Roger Pannell.15,29 An analysis of the parish rate books by Arthur Rowe gives a list of the occupiers of the mill from 1716:30

1716-1717 Thomas Pannell

1717-1725 Roger Pannell

1724-1725 Mr Cowell (probably Benjamin Cowell the Elder)

1725-1730 John Webb

1730-1733 Mr Dunn

1733-1747 Mr Cramp

1747-1759 Thomas Hollam (Holland)

1759-1772 Thomas Doorn (Down) (pulled down)

In 1772 the mill owned at the time by Benjamin Cowell the elder, was removed by his son John Cowell to a new site where Thanet House was later built; the mill was eventually demolished in 1789.30 The reason for moving the mill was given in the Canterbury Journal:31

Last week a Windmill belonging to Mr Cowell, at Margate, was obliged to be moved a further distance from the town. The many new houseslately built near it obstructed the wind in such a manner that it could not work.

Amongst the lime kilns, herring-hangs, and the windmill at the upper end of the High Street were a number of malt houses. In 1766 an advertisement appeared for the sale of the property of the late William Jarvis, a Margate maltster:32

A freehold estate, lately the Property of Mr William Jarvis, Maltster, deceased, consisting of a large good Dwelling House containing three Parlours, three Chambers, two Shops two Kitchens, two Cellars, &c. together with a large Malt-house, that wets 20 Quarter per Week, also a Brewhouse, Stables, and other Out-houses, Yards, Gardens, &c. situated at the upper End of High-street, near the Church in Margate, very commodious, and capable of great Improvement.

A malthouse and a brewhouse at Church Hill, owned by Henry Petken and then by his son William Petken, brewers and maltsters, are also mentioned in mortgages of 1719 and 1737.33 These talk of ‘outhouses, malthouse, yard, garden etc. and two pieces of arable land about 8 acres, at or near St John’s Church hill, in tenure of Henry Petken’ and also of ‘copper tuns, barks, float, brewing vessels, great and small casks, utensils, implements of brewing, horses, carts, and dray.’ It is not known whether or not this was the property later owned by William Jarvis. Henry and William Petken were major figures in Margate, both, at one time, being Deputies of the town (Appendix I);34 they also had the original brewery on King’s Street that was later to become Cobb’s Brewery. An indenture of 1743 refers to a tenement owned by William Petken ‘commonly known by the name or sign of the Five Bells, late in occupation of Abraham Mummery, victualler, at yearly rent of £4 5s’.33 The Five Bells was a popular place used for entertaining by the Parish Overseers, first appearing in the Parish rate books in 1698.35 It seems likely that the Five Bells was the public house later to become the Six Bells, the public house that once at the top end of the High Street, facing the Church.

|

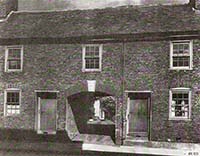

Figure 14. Buller’s Court in 1939. |

|

Figure 15. Old houses at the top of the High Street before demolition, looking towards the 'Hope and Anchor'. |

|

Figure 16. Old houses between the Six Bells and the west gate of the Church. |

Little is known about the houses at Church Hill; none of the old buildings now survive. An indenture of 1671 refers to ‘all that messuage in Church hill and commonly called Jumble House, now or later in occupation of Edward Cobb’,36 an intriguing reference given the fact that a group of old houses in this area were later referred to as ‘Jumble Joss Island’. Opposite the Six Bells was Buller’s court; photographs of Buller’s Court show that it bore a stone plaque above the archway leading into the Court, with the words ‘Bullers Court, 1673’ (Figure 14). John Lewis describes how, in 1673, Francis Buller gave to the Parish ‘several tenements, and half an acre of land, lying at Church-hill, the rents of which are to be laid out . . . in binding poor boys apprentices to some sea-faring employment’.1 Buller’s Court came to be used to house the poor, as described in Chapter 4. Further down the High Street, on the corner of High Street and Church Square, was another old courtyard, called Dixon’s Row on Edmunds map of 1821, but Dixon’s Place in a street directory of 1883.37 Rowe reports that this also bore an inscription, this time in the form of a brick insert ‘E.B. 1676’. Close by was Dixon’s Court; a sale of the estate of the late James Dixon in 1831 included a house at the entrance to Dixon’s Court, No. 69 High Street, containing nine ‘large airy rooms’.38 Edmunds 1821 map shows the One Bell public house in the northern corner of Dixon’s Court. An entry in the records of the Overseers of the Poor for 1733 shows a payment to ‘Mr [William] Simmons for half years rent for the house at the Signe of the Bell’ ; Rowe suggests that the overseers probably paid Simmons, a local brewer and maltster, for the use of one or more rooms in the inn as a parochial office.39 An indenture of 1777 for James Dixon speaks of ‘the shop formerly a smith’s forge and now a wheelwrights shop’ and an indenture of 1664 between John Parker and Josiah Simmons speaks of ‘a small piece of land with smiths forge’; it is not known whether the forge was in Dixon’s Row or in Dixon’s Court.38,40 The deeds of the old houses between the Six Bells and the west gates of the Church (Figures 15, 16) show that they date from before 1696.24

Land on the opposite, west, side of the High Street, between the modern Grosvenor Hill and Marine Gardens, was also sold off in the middle years of the seventeenth century. In 1650 Alexander Norwood sold 11 perches of land to John Hodges, yeoman; by 1781 Isaac Covell had built four messuages on this land, later referred to as Covells Row and found between Nos. 132 and 134 High Street.41 Three years earlier, in 1647, Alexander Norwood had sold 8 perches of land for £4 to John Spratling, ‘mariner of St John’s’; this was adjacent to the 11 perches of land sold by Norwood to John Hodges, land on which Hodges ‘soon after built a messuage, still standing [in 1680]’.42 These properties were to become No. 122 High Street; Nos. 122A and 124 were later additions built in the yard attached to No. 122.42 Further down we come to Nos. 106A and 106B High Street, in Prince of Wales’ Yard. These properties were built on some of the 40 perches of land sold by Alexander Norwood in 1647 to Henry Samways, a gentleman of the Parish of St John’s, for £5.43 The land already contained ‘two old thatched cottages and a draw well’. That the cottages were referred to as old in 1647 suggests that they could have dated back to the sixteenth century, and the selling price of £5 for the land and two cottages suggests that they must have been pretty ramshackle. On a further portion of Samways’ 40 perches of land were built what later became Nos. 98, 100 and 102 High Street.44

The picture we are left with is of a highway from the Church to the harbour that, before Norwood’s great sell off of land ran through open fields with just an occasional thatched cottage. Even after the selloff, plots of land were slow to be developed, and the many herring hangs and malt houses, not to mention the local lime kilns, scattered along its length well justified the judgment of future generations that it was ‘but a long dirty lane.’ It is not certain that much better can be said about the other King’s highway, the one that was to become King Street.

The second King’s highway ran from the Pier to Lucas Dane; to the north of the highway, running up to the Fort and the cliffs, was arable land. Lining the highway were a number of the more prestigious houses in Margate, together with malt houses and at least one brew house, later to develop into Cobb’s brewery. At the corner of the future King Street and Fort Road (previously Fountain Lane) was the Fountain Inn, later the site of Cobb’s Bank. The Fountain Inn extended almost a hundred feet along Fountain Lane, its odd shape reflecting its complex history.45 Part of the site, containing a house, shop and garden, belonged in 1688 to Jeremiah Fanting, described as a yeoman. The property passed to his granddaughter Mary, who was married to John Covell, who sold it to William Armstrong, described in his will as a Tavern Keeper. The neighbouring property, also a house, shop and garden, was sold by John Glover to Thomas Grinder in 1681, who then sold it to Ralph Constant in 1685; John Glover becomes important later in relation to the Mansion House. Ralph Constant’s wife Mary passed the property in her will to her three daughters, Mary Tomlin, Ann Laming and Elizabeth Pamflett. In turn they sold the property in 1731 to William Armstrong and it seems likely that he was responsible for the development of the Fountain Inn. In 1756 the Fountain was sold to George Friend and, in 1772, to Francis Cobb.46,47

Further along King Street was the site of what was to become Cobb’s Brewery (Figure 17). The site was large, extending from the highway up to the Fort. In November 1615 Richard Lee, a maltster of St John’s, acquired premises in Margate from William Parker, including a malthouse or brewhouse together with buildings and land, amounting to about 3 acres in all.48 His son, Daniel Lee, sold the property to Dame Mabel Finch, a widow of Canterbury, in 1663, at which time it consisted of land and a brewhouse, occupied by Richard May, a brewer, and a malthouse, occupied by Rowntree Cockaine.48,49 The property then seems to have returned to the Lee family as an indenture dated 1681 records the sale of the property by John Lee, a tailor of Canterbury, to William Petken, a brewer of Margate: it was described as ‘one malthouse and brew house, one millhouse, one stable, in or near a place commonly called or known by the name of Lucas Dane’. The location of the property was described as abutting ‘the King’s Highway towards the south, to the lands of Mary Wright widow towards the west, to the land of the heirs of James Trapham and to the Kings Highway towards the East, and to the Lands of John Jewell towards the North.’ An early name for Trinity Hill was Trapham’s Lane, (Figure 17) and, assuming that ‘the land of the heirs of James Trapham’ was located close to Trapham’s Lane, this locates the site of Petken’s brewery as the site of the later Cobb’s brewery. Ownership of the site becomes confused for a few years but evidently remained in the Petken family, passing from William Petken, on his death, to his wife Mary and to their two sons Henry and Thomas; on Henry’s death, the property moved to his son William Petken jun. and then, on his death, to his brother Henry Petken jun., who was now living in Dover. An indenture of July 1763 passed the property from Henry Petken jun. to George Rainer of Ramsgate and in August 1763 George Rainer sold it to Francis Cobb. The indenture of August 1763 described the property as:

all those 3 messuages, one counting house, two cellars, one washhouse, one brewhouse, and all the brewing vessels, copper implements and utensils of and belonging to the said Brewhouse, two large vaults, one stable, one malthouse, 2 dry lofts, one millhouse, two herring houses or storehouse, one summer house, two cowhouses, one coalhouse, one large Tiled lodge, three yards, 2 gardens, and a parcel of pasture land commonly called the Green which is walled in and contains ca 3 acres, and 2 small pieces of land with a carriage-way and gutter or watercourse heretofore part of a Great Backyard. All lying and together adjoining; some parts do abut bound or lye to or upon the Kings Highway or Street there leading from a certain place commonly called Lucas and otherwise Luke’s Dane to Margate pier towards the south and heretofore in the several tenancies or occupations of William Petken, John Pearse, Thomas Row jun. and Robert Brooke

The original Brewhouse was on the north side of the highway, on the site of the garden behind the house later built by Francis Cobb on King Street.50 Close to the brewery site were three large houses, two of which can be identified with some certainty thanks to a sketch map produced, probably in 1796, to help settle an argument about access to the houses (Figure 18). The map shows the passageway giving access to the brewery site from the King’s Highway; the passageway was referred to in later street directories as Brewery Hill and is now Cobb Court. On the east side of the passageway were the house and lands of Captain Brooke (probably Captain Robert Brooke), previously belonging to Richard Lister. On the west side was land belonging to the Petkens, leading up to a house probably built by Benjamin Doncaster [or Donkester] in the 1680s; in 1682 Benjamin Doncaster, a mariner, bought 6 perches of land from William Petken, together with the use of a ‘carriageway leading from the Street or Kings highway south by the lands of Richard Lister up to the Gate or doors now late built upon some of the above bargained land’.46 In 1729 Benjamin Doncaster, now residing in Petersburg, sold the property to Richard Foley, and the house took the name of Foley House. In 1688 Captain Turner (probably Captain David Turner) purchased the land adjacent to the house as a garden (Figure 18) so that it is likely that Turner occupied the house at that time.46 In 1732 both Captain Robert Brookes and Captain David Turner were Pier Wardens (Appendix II).51 By about 1796 Foley House was in the occupation of Charles Boncey, a local builder.46 His advertisement for its sale in 1807 gives a description of the house:53

A large genteel Family House, called FOLEY HOUSE, situated near King-street, Margate; consists of two good parlours, two drawing rooms, hall, kitchen, counting-house, extensive cellars, large and airy bedrooms, makes fourteen beds; coach house, stable for six horses, a good flower and kitchen garden; large storehouses, pump with fresh water, and every requisite for a genteel family, or trade.

In 1811 Foley House was bought by Francis Cobb.46 The location of the third house off the King’s Highway , the Mansion House, is less certain and its interest, together with that of its builder, John Glover, is sufficient to warrant a separate section.

|

Figure 19. The Tudor House as shown in Kidd’s 'Picturesque Companion to Margate, Ramsgate and Broadstairs and The Parts Adjacent', W. Kidd, London, 1831. |

Further along King Street we come to Lucas Dane proper which was, at this time, largely agricultural. Just beyond the future site of Cobb’s brewery, on the north side of the King’s highway, was a cart road leading to Northdown, shown on Edmunds map of 1821 as Trapham’s Lane and now known as Trinity Hill. A map of 1774 showing the land owned by Charles James Fox in this area shows a house with a malt house and garden on the east side of the junction of the cart road and the King’s highway, with land extending up to the cliffs; the house was later to be known as the Tudor House (Figure 19).54 The Tudor House has a complex history dating back to the sixteenth century or before.55 Abstracts of deeds date the house back to 1681 when it was sold to Thomas Grant, a mariner, by John Savage, another mariner; at the time the house and land was rented by John Laming, a member of a wealthy family of Margate ship-owners. John Savage was probably the son of William Savage who died in 1662;56 William Savage was a wealthy mercer, a mercer being a merchant, especially one involved in the export of wool and the import of luxurious fabrics such as velvet and silk.

The indenture of 1681 between John Savage and Thomas Grant suggests that by then the house was used as a farmhouse. The indenture describes a cart way 8 feet in breadth through the land to allow ‘horses, carts and carriages to pass up and down from the messuage lands . . . unto the King’s highway adjoining to the lands of the said Savage’, it being this cart way that eventually become Trapham’s Lane.56 The land and buildings were sold by Thomas Grant in 1687 to Stephen Higgins, a London victualler, who leased them in 1714 to Valentine Denne, a yeoman of Reculver; at this time the ‘tenement, garden, malthouse, barns, stables, Podwarehouse [the meaning of ‘Podwarehouse’ is now lost], storehouse, cellars, court yards, backsides, orchard, garden, well house, outhouses, edifices . . . and parcels of arable and pasture land’ occupied about 23 acres and were in the tenure of John Castle. A sale of the farm in 1741 refers to ‘the farmhouse wherein John Castle then or lately did dwell’, the first time that the house was explicitly referred to as farmhouse; a sale of the property in 1770 to Henry Lord Holland also refers to ‘all that farmhouse where John Castle did dwell’.56 A document of 1790 again refers to ‘all that messuage or farmhouse where John Castle [used to] dwell’ but then adds that it had been ‘converted into dwellings’.56 This is probably the state of the house shown in Kidd’s Guide of 1831 (Figure 19). Finally, in the early 1800s Fort Crescent, East Crescent Place, and West Crescent Place were built by Claude Benezet on the 20 acres of land originally belonging to the farmhouse.56

Another large farm in Lucas Dane was owned by James Taddy, a Margate mariner. In 1705 James Taddy married Susannah Laming, the daughter of Peter Sackett, a yeoman also of Margate, and Taddy, on his marriage, settled the farm on himself and his new wife.57 The farm was described as ‘all that Mansion House . . . with kitchens, barns, stables, gardens, orchard, backsides, court, yards, and appurtenances . . . also nine several pieces of arable land to the said messuage belonging, containing ca 40 acres . . . at or near a place called Wilds Dane or Lucas Dane and now in the occupation of John Cowell.’ In an indenture of 1733, the house was described as a farmhouse rather than as a Mansion House, and included a malthouse along with all the other buildings.57 The property remained in the Taddy family until 1795 when it was sold to Francis Cobb the younger.57 Unfortunately, the exact location of the farm is not known.

Behind the buildings facing the harbour was what is now referred to as the ‘Old Town’ (Figure 9). Unfortunately it is difficult to identify particular streets and buildings at this time as the requirement to name streets and number houses was only introduced in 1787 with the Margate Improvement Act. However, comparing Lewis’s drawing and Harris’s Map with modern maps of the town shows that as well as the buildings facing the harbour and those along what were to become High Street and King Street, houses had been built along another street running inland, later to be named Market Street. The site of the present Market Place was originally an open space called the Bowling Green. Lewis reported that ‘in 1631 I find a Market was kept [in Margate], of which a return was made to Dover every month, but this seems not to have continued long, nor does it appear by what authority it was kept at all’.1 The early market referred to by Lewis would have been just a series of market stalls for produce such as fruit, vegetables and meat, lining a street or an open space such as the Bowling Green, much like a modern street-market. The principal public and official buildings in many country towns came to be built around the market place, and a covered space would often be provided for the market stalls; often a hall or court room would be built above the market.58 This was the pattern of development at Margate, although the town had to wait until 1777 for its permanent market building, which was built on the site of the Bowling Green. A legal document of 1789 refers to buildings ‘near the place there formerly called the Pier Green since called the Bowling Green and then called Market Place’, 59 but this sequence of names seems likely to be wrong. An indenture of 1641 refers to a messuage ‘called the Queens Arms [abutting] a place called the Bowling Green’,60 and, since the present Queens Arms abuts the Market Place, this seems to confirm that the site occupied by the Market building was originally called the Bowling Green. Pier Green was the name used for a piece of land near the Pier and the papers in a legal case of 1755 describe how some time before the 1750s a storehouse had been built on a part of the Pier Green that had been used as a sawpit, and that the sawpit was then moved to the spot ‘where the Market now stands’.60 It is possible that the original name of Bowling Green was changed to Pier Green when the sawpit was moved to the Bowling Green site, but, if so, the name did not stick as deeds of 1705, 1729, 1765, 1768, and 1789 and a lease of 1765 all refer to the Bowling Green.62,63

Buildings around the Bowling Green were likely to have been mostly commercial premises. Rowe describes the deeds of an old butcher’s shop in the Market Place, Dale and Son, that was originally a herring-house, but was bought in 1707 by John Barnett, a butcher; Rowe established that the premises were certainly a butcher’s shop by 1752.24 An indenture of 1632 between John Bunson and Nicholas Woolman records the sale for £300 of the Old Kings Arms, ‘close to the green called the bowling green’, and, on the back of the indenture, someone has written ‘the Queen’s Armes’.64 The indenture of 1641 already referred to describes the Queen’s Arms as abutting on the Bowling Green, so that we can be fairly certain that the Old Kings Arms was an earlier name for the Queen’s Arms.

Leading into the Market Place was Puddle Dock, now called Love Lane, a lane lined by herring hangs and stables.24 At the corner of Love Lane and the Market Place was the Old Crown, mentioned in deeds of 1776.63 In neighbouring Lombard Street a brick building, still there, is decorated with small brick arches and pilasters and dates to the late 17th century, and must have been a prestigious house when it was built.65 The will of Edward Diggs in 1725 refers to five messuages ‘at or near Pier Green’ and a legal document of 1811 makes clear that these properties were in Lombard Street.59 In 1730 Jeremiah Jewell, of East London and John Jewell a Margate mariner sold 5 messuages on the south side of Lombard Street, ‘of yearly value 22 pounds ten shillings, now or late in the occupations of Thomas Slayton, Richard Laming, John Culmer, Thomas Burnell and Wm. Pain’, including a herring hang, to Stephen Swinford, another Margate mariner.66 Lombard Street was one of the earliest streets in Margate to bear a name, as indentures of 1738 and 1750 refer to ‘a certain street in Margate there called or known by the name of Lombard Street’.67

The Mansion House and John Glover

The location of the third of the large houses off King Street, the Mansion House, is uncertain because the house was demolished before the publication of the first detailed map of Margate, Edmund’s map of 1821. The most likely site for the house was on the east side of Fountain Lane at the point where Fountain Lane became a footway, as illustrated in Figure 20. The strongest evidence for this being the location comes from an indenture for the sale of the house in 1768.47 This describes the sale of:

all that messuage or Mansion House heretofore erected and built by John Glover, together with the outhouses, etc. securing and reserving the several rights of the respective owners of several messuages situate at or near a certain passage belonging to the said messuage or Mansion House, and then in the occupation of Anthony Walton, John Price, Richard Goadson, Joseph Griggs, Abraham Hedgecock, and Thos. White to the use of a way to go into and out of and from the back doors, of the six several messuages or tenements, by and through the aforesaid passage leading from the Street between the messuages there of John Gore, and a messuage there of Geo. Friend, known by the name of the Sign of the Fountain, up by the said messuage or Mansion House, and also from thence towards and up to the Fort Green there. . . . And also reserving to such persons who should be owners of the new-built messuages, standing in the aforesaid passage, in the occupations of Daniel Rose and Edw. Goatham, the right to the use of a way by and through the said passage (that is to say) a carriage and footway to and from the street, to and from the houses, and to and from the same houses to and from the Fort Green aforesaid only a footway.

The six messuages referred to here are the six houses shown in Edmunds map of 1821 making up the row of houses between Pump Lane and Fountain Lane. The passageway, later called Fountain Lane, ran from the King’s Highway or Street, later called King Street, along the side of the Fountain Inn. Edmunds map and the Ordnance Survey Map of 1852 shows that, just beyond the six messuages, Fountain Lane changed into a footway leading to the Fort. As described later, the Mansion House eventually passed into the ownership of Matthew and Stephen Mummery, who pulled it down and built a coach-house and stables on the site.47 All this suggests that the Mansion House was located on the east side of Fountain Lane at the point where it became a footway, as suggested in Figure 20.

The indenture of 1768 that has just been quoted continues:47

And also reserving to Francis Cobb, owner of a certain storehouse standing also in the said passage, to use of the passage, with liberty to turn any carriage in that part of the passage leading from the street to the entrance of the courtyard of the said Mansion House. And also reserving the use of the Pump standing near the said two new-built houses and the water thereof, and also the privilege of going in and out of the Great Gate standing in the same passage near to the said Pump, leading to a Lane called Pump Lane for the use and benefit of the said two new-built houses, the owners of the said two houses paying a proportionate part of the repairs of the said Pump and Gate.

The Pump, after which Pump Land was named, was located in a recess on the west side of Pump Lane opposite the Fountain Inn, where the old Ambulance Station building of 1896 was erected in what by then had become Fort Road.47

The story of the Mansion House starts in 1672 with the sale by John Crispe to John Glover, gentleman, for £150 of ‘all that messuage with the shop, outhouse, buildings and gardens, in Margate, towards the street there south, towards the Highway leading from the said street west and towards the messuage of Robert Brooke east’.48 The ‘street there south’ was the King’s Highway, later King Street. A second indenture, dated 1677, records a grant and demise [lease] by John Glover to Henry Yeates of ‘all that capital messuage then lately erected with all and every the outhouses buildings Court yards gardens and green spot of Grounds thereunto belonging, whereof part was then lately purchased by Jeffrey Tomlin gentleman.’ The indenture goes on to detail ‘one large capital messuage or tenement then lately erected and built by him and wherein the said John Glover then dwelt…’ and a ‘garden and orchard, together with the dove house, brewhouse and other outhouses’.48 The indenture suggests that John Glover over-extended himself financially in building the Mansion House and, indeed, in his will of 1681 he suggests that his wife Susannah should, if necessary, sell ‘the messuage and premises’ to pay his debts.47,68 During a court case of 1716 it was reported that about three years before the death of Susannah Glover, to whom the house had passed, Nicholas Constant ‘did hire from her half of the said house for which he gave the yearly rent of £8’.

The land referred to above as ‘lately purchased by Jeffrey Tomlin gentleman’ was probably at the north end of the site, close to the cliffs (see Figure 17). A document of 1697 records the gift by Jeffrey Tomlin, of St Peter’s, to William Goatham, brewer, in 1697 of ‘my chalk wall containing fourteen roods be there more or less with the ground whereon the wall standing . . . at or near a place there called the Fort Green’ separating the land of William Goatham from Fort Green.48 A rood, or rod, was a measure of length equal to about 16 feet,70 so that the length of this wall was about 224 feet. This matches the length of the wall shown on Edmunds map of 1821 separating the top end of the Brewery site from the Fort (Figure 17) and shown in Oulton’s print of 1820 of the Brewery (Figure 21).

John Glover died in 1685 and his wife Susannah died in 1713.71 In the court case of 1716 that followed Susannah Glover’s death, the Glover’s house, ‘commonly called the great house in Margate’ was described as ‘the largest and most capacious house in Margate’.69 The house had often been used by ‘persons of quality’ on their journeys from England to Holland or France.69 John Evelyn records in his diary on March 27 1672 that on a visit to Kent he stayed at Margate and ‘was handsomely entertained and lay at my deputy’s Captain Glover’.72 In a letter of November 1677 to Sir Joseph Williamson, John Glover reported that ‘last night, the wind being S., the Prince and Princess of Orange went on board Sir John Holmes and stood off to sea, but, the wind coming N.E. in the night, they came back again into this road, and about 11 this morning came ashore to my house, where at present they are in very good health’.73 In her evidence to the court case of 1716 Martha Harman, Susannah Glover’s servant, reported that ‘his late Majesty King William, his Grace the Duke of Marlborough, his Grace the Duke Shrewsbury and diverse other persons of quality and distinction in journey or passage from England to Holland or France . . . did frequently take up the said house and sometimes lodge there at other times . . . for which they used to make presents or other gratifications to the said Susannah Glover’.69 Following Susannah Glover’s death in 1713 the house stood empty while the arguments over her will were fought through the courts. Martha Harman reported that after Susannah’s death, although people of quality had been at Margate, ‘they did not stay in the House but went to the house of Mr Jewell and lodged there’.69 Confusingly, one of the London papers, Applebee's Original Weekly Journal, reported in November 1720 that: ‘Yesterday Morning, between One and Two, his Majesty landed at Margate in Kent, and lay at the House of Mrs Glover in that Town, and came to St. James’s last Night’.74 Since this was seven years after Susannah Glover’s death either her old house was again being used by ‘persons of quality’ or the paper had got it wrong.

Even before Susannah Glover’s death the house ‘was very much out of repair’ and it was reported that ‘the stable belonging to the said great house was blown down several years before the death of the said Susannah Glover’.69 Vincent Barber, a ‘house carpenter’ reported that the house ‘was unfit for any Gentleman’s use without repairing’ and that ‘the said house standing out of the way of trade and business’ was ‘only fit for a Gentleman’s use.’ Edward Constant, the Margate postmaster in 1716, reported that at the time of Susannah Glover’s death ‘the said great house, outhouses and garden were in tolerable repair sufficient for any common tradesman but not for a Gentleman.’

Following the end of the court case in 1717 the house was advertised for sale in the London Gazette:75

A good brick messuage, four rooms on a floor, situate in Margate in the Isle of Thanet in the County of Kent, with good gardens, brewhouse, stables, and other conveniences, late the estate of John Glover, Gent. deceased, is to be sold by decree of the High Court of Chancery, before John Bennett, Esq, one of the Masters of the said Court. Inquire for a particular at the said Master’s House, at the upper end of Chancery lane.

The house was finally purchased in 1721 from James Glover, son and heir of John Glover, by John Wheatley of Margate, acting on behalf of Stephen Baker, a gentleman and mariner of Margate.47 Stephen Baker died in 1751, and, in his will proved ‘on oath of Elizabeth Baker spinster’, he left money and ‘my fishing boat’ to John Baker, and money to his son Stephen and to his daughter Elizabeth.76 Although there was no specific mention of the Mansion House in his will, it was clearly passed on to his daughter as her will of 1764 declares:77

First I give and devise all that my messuage or Mansion House with all and singular the outhouses buildings yards gardens land hereditaments . . . situate in Margate . . . now in my own occupation and also all those two messuages or tenements and all that Brewhouse of building with the outhouses buildings ground . . . together adjoining near to my said Messuage or Mansion House and now or late in the several occupations of Daniel Rose, Edward Goatham and George Friend . . . and also all that Messuage or Tenement with the outhouses buildings ground . . . at or near a place now called Puddle Dock and now or late in the occupation of John Palmer together with all other my messuages lands tenements . . . real estate . . . unto Richard Ward of Woolwich in the said county of Kent, Shipwright and John Baker of the parish of St John.

Richard Ward and John Baker were to sell the property, including ‘my said Mansion House’ and to use the money for a variety of bequests specified in the will.

The house was duly advertised for sale in a London paper in 1766:78

To be sold to the highest Bidder, on Tuesday the 6th day of May . . . at the New Inn

The several messuages and tenements after-mentioned, situate and together being in the said town of Margate in several lots, viz.

Lot 1. A large Mansion-house, with four rooms on a floor, late in the occupation of Mrs Elizabeth Baker, deceased, standing upon a rising ground, so as to command from some of the upper rooms a prospect of the sea and land: the size of each room as follows, viz,

|

Length |

Breadth |

Height |

|||

|

Feet |

Ins. |

Feet |

Ins. |

Feet |

Ins. |

The Ground Floor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

One large kitchen |

20 |

6 |

20 |

1 |

8 |

0 |

One scullery with pump |

21 |

1 |

9 |

6 |

||

One cellar |

17 |

6 |

14 |

6 |

||

One cellar with pantry |

11 |

3 |

7 |

6 |

||

A place for coals |

11 |

3 |

7 |

6 |

||

The First Floor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

One large parlour with two closets |

21 |

4 |

16 |

8 |

9 |

8 |

One parlour with ditto |

14 |

7 |

12 |

0 |

||

One servants hall |

17 |

10 |

13 |

0 |

||

One back parlour |

17 |

10 |

11 |

8 |

||

A fine open stair-case with two others close |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The passage leading from the fore door |

|

|

6 |

8 |

|

|

The Second Floor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

One large dining-room hung with painted cloth |

21 |

9 |

21 |

6 |

10 |

10 |

One chamber |

21 |

6 |

15 |

9 |

||

One back chamber with closet |

17 |

8 |

12 |

0 |

||

One back chamber with ditto |

18 |

3 |

17 |

8 |

||

The Third Floor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

One large laundry |

25 |

0 |

16 |

0 |

8 |

3 |

One chamber |

15 |

8 |

14 |

6 |

||

One chamber |

18 |

0 |

14 |

7 |

||

One chamber |

16 |

0 |

14 |

6 |

||

Two small store rooms, each |

14 |

6 |

7 |

0 |

||

The garden before the house |

50 |

6 |

41 |

6 |

|

|

The back yard |

42 |

0 |

12 |

0 |

|

|

The garden behind the house |

97 |

6 |

42 |

0 |

|

|

N.B. The gardens and yard are walled in. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lot 2. One new built messuage, in the occupation of Mr Daniel Rose.

Lot 3. One new built messuage, in the occupation of Mr Edward Goatham.

Lot 4. One store-house with a vault thereunder, in the occupation of Mr George Friend, or his under tenant, the size thereof being 54 feet 9 inches by 20 feet.

N.B. The premises are all freehold.

Enquire in the mean time of Mr Richard Ward, at Woolwich, in the county of Kent; Mr John Baker, at North Down, near Margate; or Mr Daniel Marsh, attorney at law, in Margate.

The property did not sell and in 1767 Francis Cobb took the opportunity to purchase just the ‘brewhouse and storehouse and vaults’, but not the house.48 The Indenture of sale, as usual, described the location of the brewhouse property and also clarified the rights of access to it:

abuting and bounding to a building or ground of Stephen Sackett towards the East, to a building or grounds of George Friend towards the south, to a passage belonging to and leading from the Street up to the Mansion house late the said Elizabeth Baker’s and from thence to the Fort Green there towards the West, and to a messuage or tenement also late the said Elizabeth Baker’s now in the occupation of Edward Goatham towards the North, or howsoever otherwise the said premises do or doth abut bound or lye late in the tenure or occupation of George Friend or his assigns or under-tenants and now or late in the tenure or occupation of the said Francis Cobb his assigns or under-tenants which said Brewhouse, Storehouse or building and premises hereby granted and released being part and parcel of the said messuages, lands, tenements and hereditaments before mentioned to be devised by the said Elizabeth Baker to be sold as aforesaid and were heretofore the estate and inheritance of the said Stephen Baker deceased and are part of the estate purchased by John Wheatley of James Glover and others by indentures of lease and release in trust for the said Stephen Baker – and also the free use liberty privilege and benefit from time to time and at all times hereafter of a way in over and through the passage aforesaid belonging to the said Mansion house from the street to and from the said Brewhouse, Storehouse or building and premises for the said Francis Cobb, his heirs and assigns and his and their tenants servants and workmen to pass and repass in over and through the said way with horses, cattle, carts and other carriages . . . and liberty at all times to turn any carriage in that part of the said passage leading from the street to the entrance of the Court yard of the said Mansion house. And also the free use . . . of a footway from the said Brewhouse Storehouse or buildings and premises in over and through the said passage up by the said Mansion House to and from the Fort Green aforesaid for the said Frances Cobb.

The Mansion House itself was advertised again in 1768, this time in the Kentish Gazette, and with less detail:79

TO BE SOLD; By Public AUCTION, to the Highest-Bidder, at the Mansion-house after mentioned, on Monday the Twenty-second Day of August Inst. between the Hours of Four and Five o’clock in the Afternoon,

The said MANSION-HOUSE (being Freehold) having four Rooms on a Floor, Closets, and other Conveniences, Two Gardens walled in, viz. a fore Garden and a back Garden, and all other Appurtenances to the same belonging, situate in Margate, upon a rising Ground, so as to Command, from some of the upper Rooms, a prospect of the Sea and Land, late in the Occupation of Mrs Elizabeth Baker, deceased.

And in two separate Lots, Two New-built MESSUAGES or TENEMENTS (being likewise Freehold) situate also in Margate, near to the said Mansion-house; now in the several Occupations of Daniel Rose and Edward Goatham. For further Particulars enquire of Mr John Baker, at North Down, near Margate, or Mr Daniel Marsh, Attorney, at Margate.

The house was bought at the auction by Thomas Smith for £400, on behalf of Holles Henry Bull of Strand in the Green, Chiswick.47 It remained in the ownership of the Bull family until 1792 but toward the end was occupied by Francis Sackett who ran a boarding house there. Sackett advertised the attractions of the ‘Royal Mansion’ in 1788:80

Royal Mansion,

At Margate in Kent, near the Play-house

Francis Sackett begs leave respectfully to inform the Noblemen, Ladies, and Gentlemen, that he keeps a good table, and other accommodation at the following terms, viz;

|

£ |

s |

d |

For the first floor per week |

1 |

8 |

0 |

Second floor ditto |

1 |

6 |

0 |

For boarding, without Lodging |

1 |

1 |

0 |

For boarding, without Lodging |

|

4 |

0 |

The reference to ‘near the Play-house’ refers to the location of the original Margate playhouse, at the Fountain Inn.81

Following Bull’s death the house was advertised for sale in The Times, in 1791, by which time it was known as Sacket’s Boarding House;82

For sale at Bensons Hotel . . . Large freehold mansion house with four rooms on a floor, known by the name of Sacket’s Boarding House; situated near the Fort, standing on a rising ground, so has a command from some of the rooms of a prospect of the sea and land, the busy picture of the London Commerce passing in Review, capable of great improvements. A garden behind the house 97 feet 6 inches by 42 feet, with a door that opens into the Fort. Back yard 42 feet by 12. The approach from the Street is a Coach road to the House, inclosed with iron gates. A flower garden in front, walled round, 50 feet 6 inches by 41 feet 6, with a flight of stone steps. Coach house with stabling for two horses, and loft over.

The above premises are fit for the reception of a genteel family.

The corresponding advertisement in the Kentish Chronicle of June 14 1791 is the same as that in The Times , but incudes full room dimensions, exactly matching those in the advertisement of 1766 quoted above.83

The house was bought in 1792 by John Mitchener, of the New Inn, and John Drayton Sawkins.47 It is possible that the House was then occupied by a school teacher, Mrs Peacock, who advertised in 1796 that ‘Mrs and Miss Peacocks – Mansion House – school recommences on 25th’.84 However, in 1803 it was sold by Mitchener and Sawkins to Matthias Mummery, a Margate coachmaster, and Stephen Mummery, a Margate farmer.47 An indenture of 1809 reported that ‘Matthew and Stephen Mummery had pulled down the Mansion House, and on the site and grounds thereof had built . . . coach-houses, stables, and buildings’ referred to as being ‘in or near Pump lane and Fountain Lane’, and that they had used the property as a security for a loan of £2500 from Francis Cobb and Francis William Cobb; in 1816 the Mummerys were declared bankrupt on a petition of the Cobbs.47

A little is known about John Glover, who built the Mansion House and was a man of some standing in Margate. In the parish church was a memorial to ‘John Glover, Gentleman, who died at London in 1685, aged 56 years, born in 1629’; an inscription underneath recorded the death of his wife, ‘Mrs Susanna Glover, his wife, Obiciit in 1713, aged 75 years’.71 At the time of his death he left an estate worth some £2000, with shares in a number of ‘good ships and vessels’.69 In 1656 John Glover had been made master of one of Oliver Cromwell’s ships:85

To Commissioners of Admiralty and Navy. Our will and please is that you forthwith make and direct your warrant to John Glover of our Isle of Thenet in our Countie of Kent gent authorizing him to bee Master and Commander of our shallop called The Welcome of our Port of Margate in the said Isle, for our special and ymediate service at sea. Given at Whitehall the Nineteenth day of February 1656.

This was a position of no little importance because of the extensive naval activity off the coast of Margate at the time, resulting from the three wars fought with the Dutch during the years 1652 to 1674 (Chapter 6). At one time he was also postmaster at Margate, but a petition to the Privy Council in 1658 shows that, about this time, he was in some trouble:86

April 22 1658. Petition of John Cockaine, John Hill, and Hen. Giles, to Privy Council.

Being ordered to appear before you, to give evidence on a charge against John Glover, officer of Margate, Kent, we have attended 12 days. Being very poor, and having large families, we beg speedy hearing or dismissal till required, and an order that Rich. Bartlet, surveyor of Customs at Gravesend, may then appear.

The nature of the charge is unknown, but a letter of 1660 from the Council of State to the Commissioners of Customs describes John Glover as ‘late postmaster’ at Margate and suggests that the the Commissioners of Customs might like to think about dismissing him from his job with them as searcher and waiter at Margate:87

January 28, 1660. Council of State to the Commissioners of Customs. Being informed that Jno. Glover, customer and searcher at Margate, and late postmaster there, is very intimate and holds correspondence with disaffected persons, — whereby, if he be continued in that employment, danger may ensue, — we have removed him from the office of postmaster there, and appointed Nich. Hooke in his stead. We recommend you to remove Glover from being customer and searcher of that port, and to put Hooke into the employment, if you hold him qualified.

There is no record of whether or not Glover was in fact dismissed from his post with the Customs at Margate, but there is a record in 1672 of his appointment as commander of a Customs smack at Margate:88

The Treasury Lords to the Customs Commissioners to employ Capt. Glover as commander of a Customs smack to be settled about Margets and Ramsgate: with an establishment of £306 per an. for himself, one mate, 6 men and a boy for said smack.

This appointment was short lived as in 1675 it was decided to remove the smack at Margate and instead for the ‘smack at Quinborough [Queenborough] to have the inspection of the Isle of Thanet insead of . . . Mr Glover’; Glover was then dismissed ‘as an unnecessary officer’.89 >

Glover’s period as commander of a Customs smack coincided with the third of the Anglo-Dutch wars, from 1672 to 1674 (Chapter 6). During this period Sir Joseph Williamson, Under Secretary to the Secretary of State, headed the government’s intelligence network of informants. He had correspondents in almost all the ports along the east and south coasts of England, many of whom were customs officers, and one of them was Glover (Appendix III).91,92 Williamson’s informants were not paid for their work but often received a copy of his manuscript newsletter, an important source of news at a time when the only licensed news sheet, the London Gazette, carried no domestic news worth reading. Informants were instructed to write to Williamson by every post, as acknowledged in the first of the letters sent by Glover to Williamson on May 10 1672:93

May 10, 1672. Margate.

John Glover to Williamson. According to the directions of yours of the 8th I will give you an account daily. Just now came about the Foreland two Holland men-of-war, and a great flyboat, which I conceive is a fireship. They all lie loose with their sails baled up, and have stopped two billanders that were coming in upon the Foreland. The whole fleet are at the back of the Goodwin. If the ships you spoke of come over the flats, it will be very dangerous

if these Dutch ships continue on the Foreland; but if it be resolved they shall come, I will have lights kept on the two buoys, that they may come through by night as well as by day. I am just going to the Foreland.

He then wrote again the same day:

May 10, 1672, 2 pm. Margate.

John Glover to Williamson. Since my last by Mr Langley's express [the postmaster at Margate] I have been at the North Foreland and on the lighthouse, which is the best prospect we have, and while there another ship came in upon the Foreland, and spoke to the three I mentioned in my last, and after they had lain by about half an hour they made all sail, and stood off the Foreland again, carrying with them the billanders they stopped, and, I presume, they will go off to their grand fleet, which lies off the flats of the Foreland, and at the back of the Goodwin. These are all the ships that were in sight, only one great ship was between the Northsand head and the Foreland, but she stood off when she saw the others stand off too. It is very hazy, with wind N.N.E., so that we cannot see far to sea, but about sunrise this morning the whole Holland fleet was seen at the back of the Goodwin, and about 30 nearer in upon the Foreland than the rest. If the ships yet in the river are ready to come down, my boat shall ply off the Foreland and inform me of all ships there, and I will contrive, by boats placed from the Redsand to the two buoys of the Narrow with lights in them, and by lights at the two buoys, that the ships shall come down as well in the night as in the day, and then those ready may be at the Foreland before daylight, and if any of the Holland fleet be there, it will not be above four or eight sail, for they never come in with more. If you will tell his Majesty he will doubtless understand the management of the affair, and if it be concluded pray send me orders what I shall do, and I will consult the commanders about it, and doubt not to bring them down safe. I will send you an account every night by express of what happens here in the day, so pray write to the postmasters to forward them. I guess the biggest ship here not to have above 50 guns, and the rest 20 or 30 apiece.

In his next letter, of May 11, John Glover explained that he had to send his letter via Sandwich, as mail from Margate was only sent out on Tuesdays and Fridays.93Despite these problems Glover managed to keep up a regular stream of letters to Williamson, although most contained little of interest.

In November 1672 John Glover wrote to Williamson asking for a job, either as postmaster again, as Richard Langley had just died, or as a customs officer:94 ‘Mr Langley is dead, and the post place here not yet settled, but let me receive your commands, and I will serve you what I am able, but the Commissioners of the Customs have deprived me of my employment in the smack, which I hope you will be a means to restore me to, when you hear my case’. In 1675 he asked for a reward of £52 for having seized a load of wool and a small boat:95 ‘John Glover of Margate. Petition for a gift of about £52, the King’s moiety of a seizure of wool, now in the petitioner’s hands, and of a small boat forfeited for importing fish. Was often employed during the late Dutch war to go on board his Royal Highness with letters and messages as he and Sir J. Williamson can testify, his charges being above £60.’

With the end of the third Dutch war in 1674 the regular correspondence between Glover and Williamson came to an end, but there is one final letter of interest, concerning religious dissenters at Margate, whose meeting houses were referred to as conventicles:96

February 12 1675. John Glover to Williamson

The fanatic party are building a conventicle house here where we never had any before, and I know not why they go about it now unless it be in spite of the proclamation against them. They make great haste to get it up, and I tell them it may be it will be pulled down as fast ere long.

This was probably a reference to the Baptists. There was a Baptist church in Dover in 1654, and the Baptists met in the Isle of Thanet in a chalk pit at St Peters; the first Baptist chapel was built in Thanet in 1690 by Stephen Shallows, at a site known by his name.97,98

Inns and Innkeepers

Margate in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries enjoyed some renown as a port of embarkation and disembarkation for the Low Countries (Chapter 2). Travellers using the harbour would sometimes need overnight accommodation and somewhere to eat and drink, facilities provided by the local inns. Inns also served as staging-points for carriers and coaches and, in the absence of other public buildings, as places where traders, farmers and ship’s masters could meet to discuss business; they also provided rooms where public events such as meetings and auctions could be held. In fact, in the years before the middle of the eighteenth century, Margate seems to have been rather poorly served with inns. A list of ‘tavernes in tenne shires about London’ published in 1636 included just two in Margate, those of ‘Averie Ienkinson and Henry [..]ulmer’.99 The second of these is probably Henry Culmer, Culmer being a common Margate name at the time; a Henry Culmer was buried at St John’s in 1661. A national survey of the accommodation available at inns and alehouses in England in 1686 found that Margate had just 27 guest beds and stabling for just 40 horses, compared for example, to 236 guest beds and stabling for 467 horses in Canterbury, and 132 guest beds and stabling for 189 horses in Dover; Ramsgate had 17 available guest beds and stabling for 19 horses.100 These numbers had, however, increased considerably by the time of a second survey in 1756, the report of which provides more information about how the survey was carried out.101 In 1693 the country had been divided into 39 areas for Excise purposes, the areas being called Collections, loosely based on County boundaries. Each Collection, under the control of a Collector, was divided into a number of districts under the control of Supervisors. Districts were usually centered in local towns, and were referred to as Divisions; the countryside outside a town was called an Out-Ride. Margate was in the Sandwich Collection, and the town of Margate made up the Margate Division, with the surrounding countryside, probably corresponding to the rest of the parish of St John’s, making up the Margate Out-Ride. In 1756 the Margate Division contained 16 inns and public houses, with 46 beds and stabling for 29 horses, and the Margate Out-Ride contained 12 inns and public houses, with 19 beds and stabling for 33 horses, giving a total of 28 inns and public houses, 65 beds, and stabling for 62 horses.101 This is somewhat more than the provision at Ramsgate, which had 21 inns and public houses, 34 beds and stabling for 56 horses, but considerable less than the 69 inns and public houses with 182 beds and stabling for 193 horses available at Dover. These numbers emphasize that the number of travellers passing through Margate at the time was still very small compared to the number passing through Canterbury or Dover, and that Margates few inns were rather small.